Surgery and fluid science combine to help dialysis in kidney disease patients

Researchers studied the blood vessels' 3D structures using Imperial's Data Science Observatory

Aeronautical engineers, medics, and bioengineers at Imperial have teamed up to predict and improve results in dialysis patients.

Their new study on 60 patients suggests that creating 3D images of blood vessel structures prior to dialysis can predict how well a patient might take to treatment.

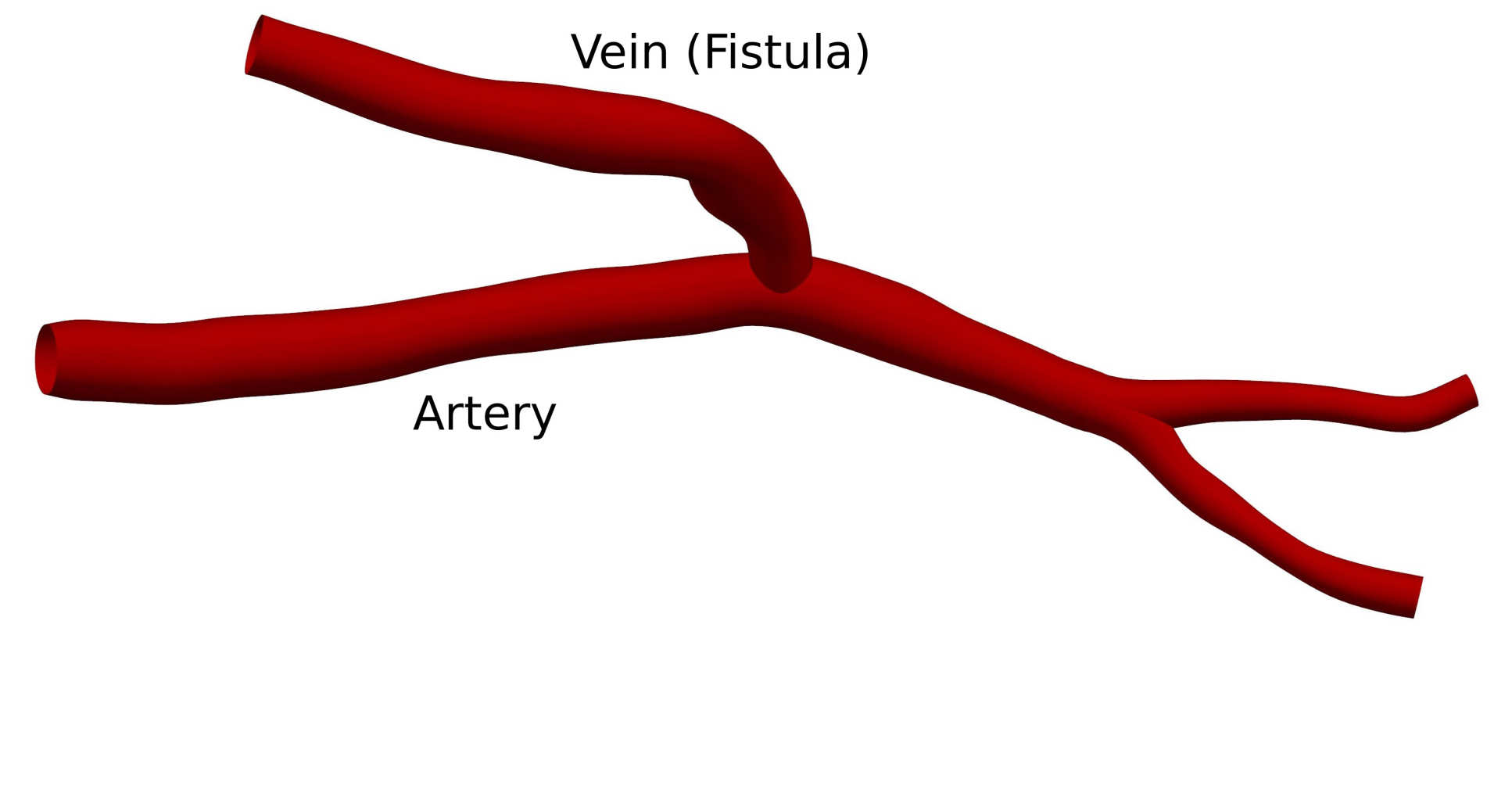

When the kidneys stop working properly, dialysis can be used to remove waste products and excess fluid from the blood by diverting it to a machine to be cleaned. To connect this machine to the patient, a surgeon creates a junction between an artery and a vein in the patient’s wrist or upper arm. This junction is called an arteriovenous fistula (AVF).

The arteries carry oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the tissues of the body, delivering oxygen to the tissues before veins take the blood back to

be re-oxygenated. The AVF rewires, or short circuits, this plumbing in the forearm, creating a ‘bridge’ between artery and vein.

After the operation, medics wait for around six weeks to let the AVF develop before beginning dialysis. If the AVF develops well the large blood vessel with high blood flow rates can be used to remove blood to pass through the dialysis machine.

However, AVFs can become inflamed and ultimately fail in around one in three patients. This means they must undergo further operations to help the AVF develop or in some cases need a completely new AVF - all of which means patients must spend more time in hospital.

Now, researchers at Imperial College London and Imperial College

We hope this will encourage surgeons who create these structures to think in three dimensions instead of two. Dr Richard Corbett Department of Medicine and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

Healthcare NHS Trust have used 3D imaging in 60 dialysis patients to measure the link between the structure of an AVF and how likely it is to fail.

To do this, the researchers used MRI scans within a few hours of surgery to measure vessel shape, create 3D images of the structures, and see whether their shape might affect success.

Dr Peter Vincent, co-author from Imperial’s Department of Aeronautics, said: “Until now, AVF are often considered as two-dimensional flat structures. We wanted to measure their three-dimensional nature, since we know this is an important determinant of blood flow patterns, and hence possibly clinical outcome.”

Six weeks later, they found that the more curved AVFs had greater success rates, as did the ones with larger angles between artery and vein.

The researchers say that by recognising the importance of the three-dimensional shape of AVFs, surgeons could help reduce the number of failed vessels and therefore improve dialysis outcomes.

Dr Richard Corbett, co-author from the Department of Medicine and Hammersmith Hospital, said: “Our findings show good reason to consider the 3D structure of AVFs when creating them in patients. We hope this will encourage surgeons who create these structures to think in three dimensions instead of two. ”

They say their broader research could help prevent AVF failure in hospitals, improving health outcomes and saving money on operations for the NHS. They also say more work is needed to identify the best possible shape for the AVFs in patients with kidney disease.

The research was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council.

“Heterogeneity in the nonplanarity and arterial curvature of arteriovenous fistulas in vivo” by Richard W.Corbett & Peter E.Vincent et al, published 29 July 2018 in Journal of Vascular Surgery.

Image credits:

Main image: Imperial College London/Peter Vincent/Data Science Institute

Article image 1: Shutterstock/sciencepics

Article image 2: Imperial College London/Peter Vincent

Article image 3: Imperial College London/Peter Vincent/Data Science Institute

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Caroline Brogan

Communications Division