"We need to think about the next pollutants" – 10 minutes with Dr Plancherel

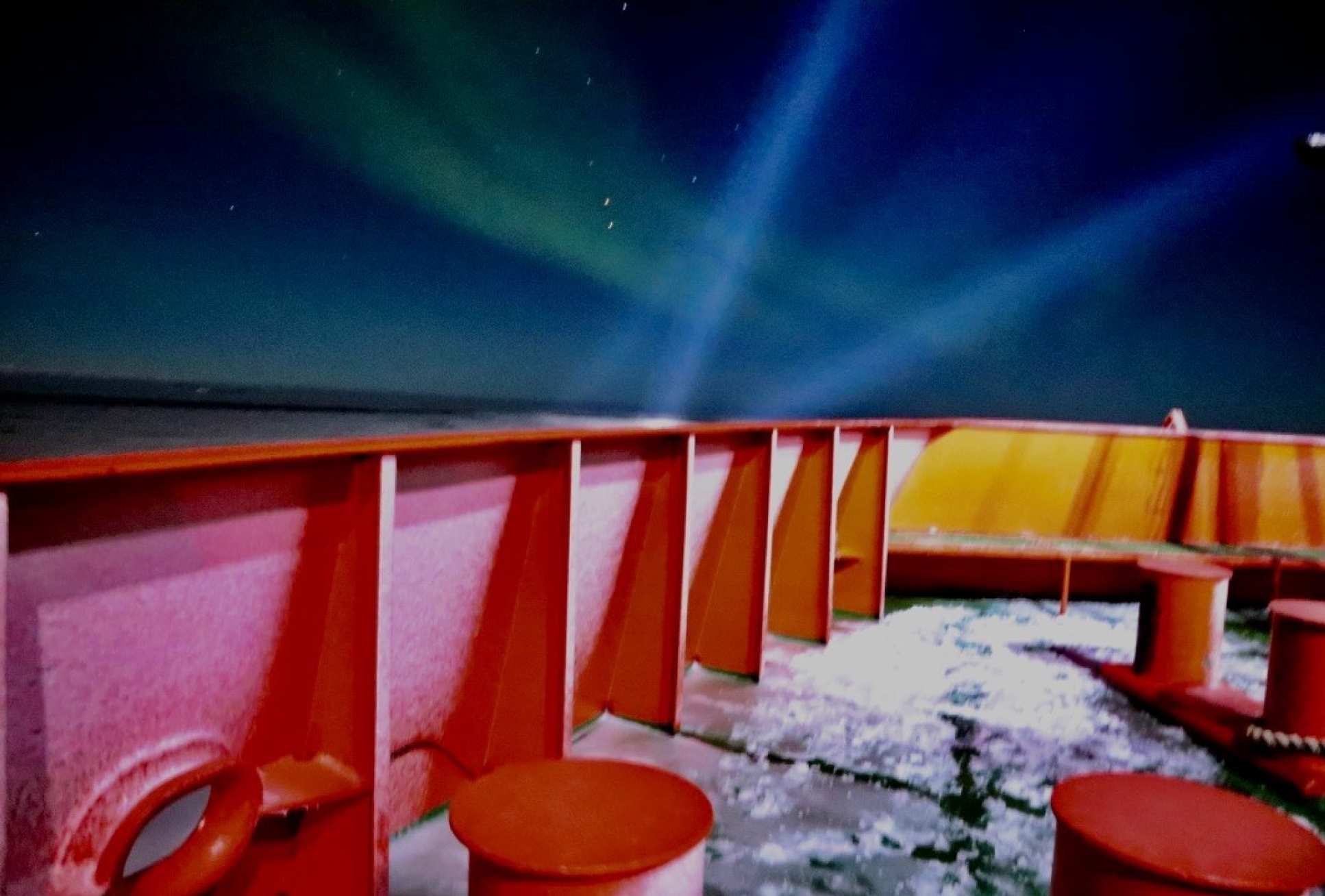

A view into the Strait of Magellan, the doorway to the Southern Ocean, on one of Dr Plancherel's fieldwork trips

New Grantham Institute lecturer says we haven't learned from our mistakes with fossil fuels, and the next problem is on the horizon.

Dr Yves Plancherel, whose research bridges chemistry and oceanography, has joined the Grantham Institute as a Lecturer in Climate Change and the Environment.

Dr Plancherel is a NERC Independent Research Fellow and former James Martin Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of Oxford. He has spent his career studying the natural processes that move elements around the environment, between soils and rocks, oceans and the atmosphere, and is now studying the potential impact of metal pollutants on the environment.

Carbon emissions weren’t considered to be a problem until we had been burning fossil fuels for about 100 years. We need to learn from that lesson, plan ahead and think about the next pollutants. Dr Yves Plancherel

While public attention is often focused on reducing global carbon emissions and tackling plastic pollution ,shifting to a low-carbon economy and using plastic in a sensible, sustainable way won’t be enough create an environmentally-friendly society.

“Carbon emissions weren’t considered to be a problem until we had been burning fossil fuels for about 100 years,” said Dr Plancherel. “We need to learn from that lesson, plan ahead and think about the next pollutants”.

We caught up with Dr Plancherel to find out more about the future of pollution, voyages to the Southern Ocean and meeting the challenge of climate change.

Did you always want to pursue a career in oceanography?

I grew up in landlocked Switzerland and many of my family never left our home town, which gave me the urge to travel. I didn’t see the ocean until I was 18, but I grew up living near a lake and religiously watching naturalist Jacque-Yves Cousteau’s films on TV– that was enough to spark an interest in marine biology. I have since diversified my research activities beyond pure oceanography but the “Cousteau-like” fieldwork aspect of ocean research that first drew me in remains attractive to me.

I grew up in landlocked Switzerland and many of my family never left our home town, which gave me the urge to travel. I didn’t see the ocean until I was 18, but I grew up living near a lake and religiously watching naturalist Jacque-Yves Cousteau’s films on TV– that was enough to spark an interest in marine biology. I have since diversified my research activities beyond pure oceanography but the “Cousteau-like” fieldwork aspect of ocean research that first drew me in remains attractive to me.

Last year, I spent over 2 months at sea, travelling through the Southern Ocean from Tasmania to Antarctica and then Punta Arenas in Chile, as part of a project to monitor how the Southern Ocean takes up excess heat and carbon. Although I can get quite seasick (something I blame on a genetic predisposition from my landlocked genealogy), every research expedition provides memorable experiences – whether it’s seeing my first icebergs, undertaking a submarine dive, weathering a big storm or having a shark encounter!

Why do you think metal will be significant as a pollutant in the future?

Energy systems, infrastructure and consumer goods like TVs, smart phones and computers all require increasing amounts of specific metals – copper, aluminium, zinc, nickel, rare earth elements and heavy metals, like lead and mercury. It is estimated that the demand for some metals will increase up to ten times in the coming decades. Even if we are able to recycle 100% of the metals we already use, we will still have to extract more to meet that demand.

Using so much metal has serious health and environmental implications – from the mining, to the manufacturing, to the recycling (or lack of). We need to start thinking about the large scale, long time effects of these perturbations to the metal cycles. Unlike many other pollutants, metals do not biodegrade.

Why are government and industry not engaged in potential pollution from metals?

At a university, we have the freedom to go beyond immediate problems and day-to-day issues, and think about long-term, maybe even hypothetical, questions. Dr Yves Plancherel

There are lots of regulations in place to limit use and release of toxic materials. Environmental protection agencies today do a wonderful job keeping pollutant levels below certain thresholds to protect people from exposure to toxic levels on a day-to-day basis. However, it is not necessarily within their remit to think about what will happen decades in the future. Long-term environmental issues are usually not on the political agenda, as they have time scales that inherently transcend not only the lifetime of politicians but also of industries.

In that sense, academic research is so important. At a university, we have the freedom to go beyond immediate problems and day-to-day issues, and think about long-term, maybe even hypothetical, questions. Environmental problems are complicated; they demand a broad, interdisciplinary approach. At the Grantham Institute, there are economists, physicists, biologists and policy experts who can all feed into research, enabling us to tackle the big, not-yet-considered questions.

What do you think has been the biggest change related to climate change and the environment over the past few years?

For me, the most notable change has been the increase in public awareness about environmental issues. Young people especially are bringing a new wave of environmental awareness into the mainstream – just take a look at some of today’s climate change lawsuits led by children. The problem seems to be with some members of the older generation – decision-makers who want to keep the status quo, because that is what they know and that is what is profitable to them. But their time is limited.

What do you do to relax and take you away from your work?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, one of my favourite activities is exploring the ocean – scuba diving and snorkeling. The aquatic world is so unseen, so new. You could go snorkeling in the same spot every day for a year and you will always see new things. In the ocean, there is always a sense of discovery.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Lottie Butler

The Grantham Institute for Climate Change