How Imperial is changing the course of COPD

To mark World COPD Day, we shine a light on recent advances in understanding and treating COPD and how Imperial has contributed.

What is COPD?

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a term used to describe a group of lung diseases – including chronic bronchitis and emphysema – which make it difficult to breathe. People with COPD are unable to fully empty the air out of their lungs and become breathless – some COPD sufferers liken it to the feeling of breathing through a small straw. COPD is a progressive disease and not fully reversible, which means it can significantly impact on an individual’s quality of life.

Traditionally tobacco smoking is thought to be the most common cause of COPD. However epidemiological observations, coupled with a new understanding of the biological mechanisms and pathways that underpin the development of COPD, is challenging the traditional perception of COPD. Air pollution, industry exposures that involve breathing in toxic particles or fumes and genetic risk factors are some of the other exposures that are known to increase the risk of developing COPD.

COPD is a disease on the rise; COPD was the ninth leading cause of death in 2016 and by 2020 it’s projected to be the third leading cause of death and the seventh leading cause of disability worldwide. It is estimated that more than 1 million people living in the UK have been diagnosed with COPD – there are also many people who have COPD who don’t even know it.

Where are we with fighting COPD?

A large body of research in COPD treatment has led to improved symptom relief for COPD patients, normally through a combination of inhaled therapies that relax the airway muscles such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Due to the progressive nature of the disease, there has been no significant development in terms of altering disease progression or survival in these patients. Many COPD patients are admitted to hospital due to exacerbations of their disease, and survival in COPD patients is lower than the general population.

Other treatments include pulmonary rehabilitation and flu vaccination, and for people who continue to smoke, smoking cessation is the most effective. There is also growing evidence that singing groups are a potential way for COPD patients to gain skills to improve control of their breathing and posture, reducing symptom burden and enhancing wellbeing.

What is the focus of current research?

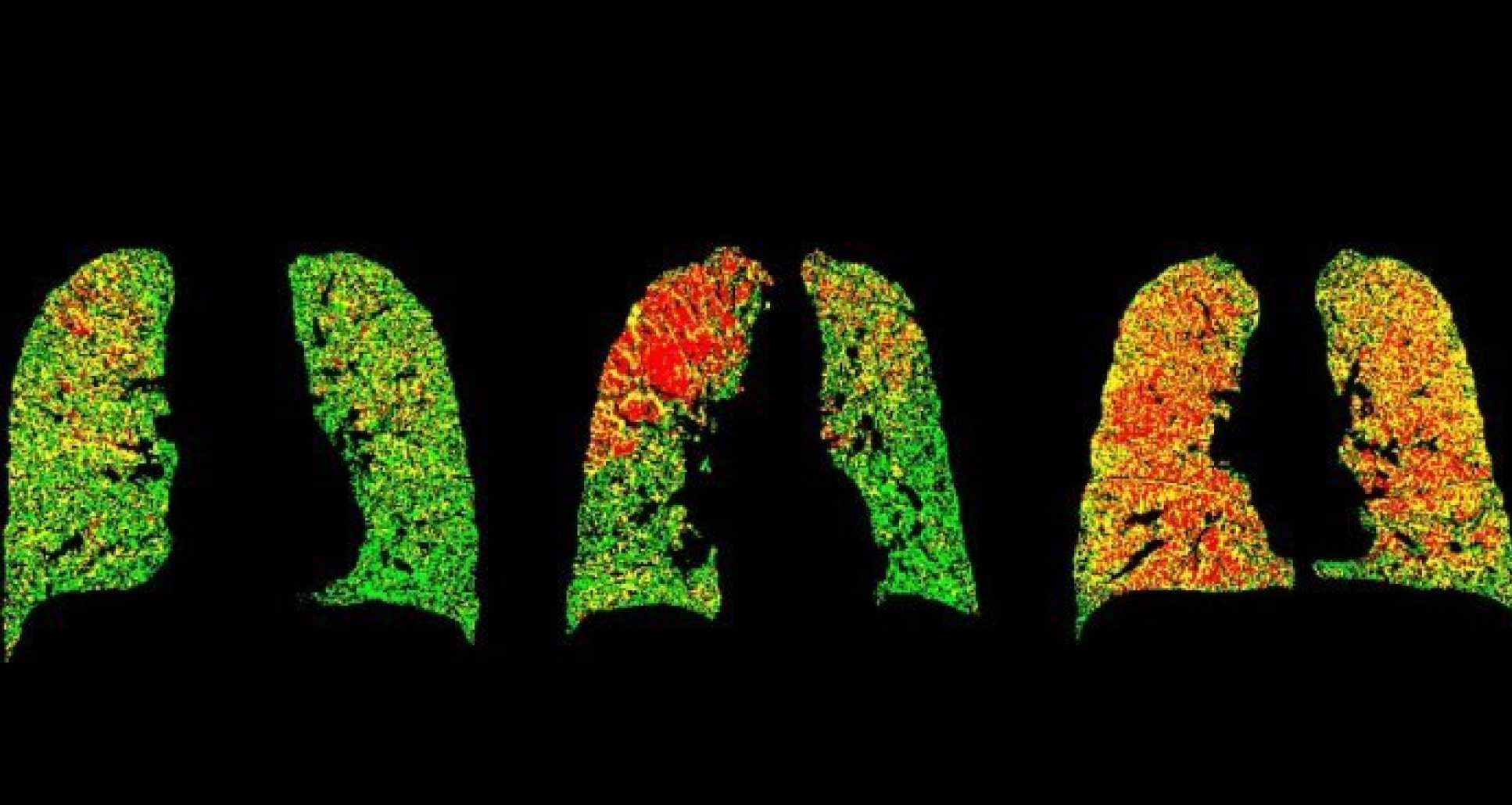

From previous research, we know that COPD is a heterogeneous disease, which means COPD outcomes can differ among patients. In order to better treat COPD patients, it is important to identify different phenotypes of COPD – the observable characteristics. A large amount of research is currently investigating different biological markers that may be associated with COPD and whether some treatments are more effective in some subgroups of patients with specific biological markers.

Furthermore, COPD treatment is aimed towards improving symptoms. Research into novel biological pathways that could be targeted with new therapies is needed. More importantly, further research into targeting pathways that could alter disease progression. Similarly, early identification and treatment of COPD is essential in improving health-related outcomes in COPD patients such as lung function decline, quality of life, and mortality. Thus further biological and pharmacological research is needed to investigate targets for early intervention and to slow or halt disease progression.

In addition, better prevention and management of COPD is needed. Many patients are still admitted to hospital every year due to the worsening of their symptoms, often due to lung infections. Survival after such hospitalisations in these patients is still very low and approximately 11% of patients die 90 days after they have been discharged. Therefore, we need better prevention and management of COPD in order to reduce the risk of hospitalisations and to reduce the risk of death.

What are we doing at Imperial?

Imperial’s National Heart and Lung Institute (NHLI) is actively involved in the study of COPD, spanning from the mechanisms of exacerbations in COPD to large cohort studies. Some of the findings across the last year include:

Early stage trials led by led by Dr Pank Bhavsar and Professor Fan Chung have shown promise for a cell-based therapy for treating lung tissue damaged by respiratory diseases. Further trials will be needed but according to the researchers, stem cells can reduce some of the damage seen in human lung cells exposed to cigarette smoke in the lab, as well as reducing similar effects in the lungs of mice.

Reducing bacterial infections for people with COPD

Dr John Tregoning and colleagues from the Department of Medicine found that people with COPD have higher levels of glucose in their airways. When people with COPD catch a virus this further increases inflammation and therefore the levels of glucose also rise, heightening the risk of a bacterial infection. This means that treatments that reduce airway glucose may have the potential to reduce bacterial infections in people with COPD, without the use of antibiotics.

Using big data to improve COPD patient care

Dr Jennifer Quint and collaborators have been awarded a grant to better understand the patient journey of those with lung disease. The researchers will be looking at data on admissions to healthcare services as a result of exacerbations to better understand the complete patient journey.

Professor Wisia Wedzicha is leading a nationwide project investigating the early stages of the development of COPD with the aim to be able to identify people at risk of developing COPD for the first time.

Why is my research in COPD important?

My research aims to investigate lung function decline – one outcome of COPD – in patients with COPD seen at the GP. Lung function decline is important as it is associated with increased breathlessness, reduced quality of life, and death. Many previous studies have been randomised clinical trials, which are not generalisable to the general population of COPD patients in the UK.

Specifically, we aim to find out what the average lung function decline is in these patients, investigate what type of COPD patient is more likely to have a faster lung function decline, and investigate what the effect of COPD treatment is in a GP population of COPD patients. We will also look at whether subgroups of patients are more likely to respond better to treatment in terms of lung function decline. This will allow doctors to identify COPD patients earlier on who are more likely to have faster lung function decline, and treat them more efficiently.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hannah Whittaker

School of Public Health