Breast cancer drug could create chink in the armour of pancreatic cancer

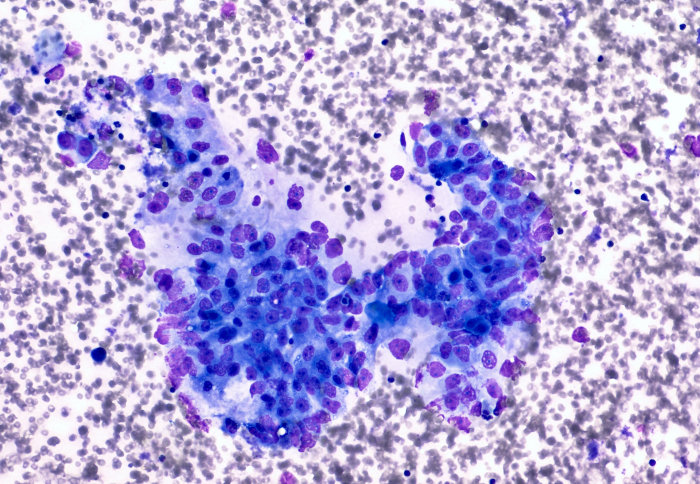

Pancreatic cancer cells, shown in dark purple

The well-known drug tamoxifen could exploit a weakness in the physical ‘scaffolds’ around tumours, according to research led by Imperial.

The report’s authors, led by Imperial College London, say that following further research, the drug might in future be repurposed to help treat pancreatic cancer as well.

For many years tamoxifen has been used to treat a common form of breast cancer by preventing oestrogen, which helps breast tumours grow, from reaching cancer cells and encouraging tumour growth.

Now, a research team, led by Dr Armando del Río Hernández from Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, has demonstrated that in mice, tamoxifen helps change the physical environment, or ‘scaffolding’, in which tumours grow. This scaffolding regulates scar tissue development, inflammation, and immune responses - three key hallmarks of pancreatic cancer.

The researchers are now keen to explore whether this previously-unseen effect could justify its use in most solid tumours, like those seen in pancreatic cancer. Their findings are published today in EMBO Reports.

Scaffolds and oxygen

Our work lays the ground for more animal studies and perhaps human trials to explore using this well established drug to treat pancreatic cancer. Dr Armando del Río Hernández Department of Bioengineering

Pancreatic cancer has a very low survival rate with less than one per cent of sufferers surviving for 10 or more years. Over the last 40 years the survival rate has not significantly changed, and finding an effective therapy is a pressing challenge for cancer researchers.

Most solid tumours, like those seen in pancreatic cancer, are surrounded by a large amount of connective tissue. The stiff, scar-like tissue stands like scaffolding around the tumour and hinders drug delivery by blocking chemotherapy drugs from reaching the tumour. It also regulates how tumours grow and spread.

The formation of this connective tissue in pancreatic tumours is driven by pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), which stiffen the tissue by applying physical forces and remodelling the tissue architecture.

The researchers looked at this scaffolding in mouse pancreatic tumours using a combination of biophysical and cancer biology methods. They found new insights about how cells that surround pancreatic tumours interact and studied how tamoxifen alters the physical environment around these tumour types.

The first paper shows for the first time that tamoxifen inhibits the ability of PSCs to harden the connective tissue surrounding tumours via a previously unknown mechanism totally different to the known pathway in breast cancer.

By preventing the tumour’s environment from stiffening, tamoxifen regulates the immune response and curbs the invasion and spread of cancer cells.

Cancer research tends to study the genetic influences on specific cancers, whereas our approach focuses on the physical factors in the environment that affect the growth and spread of tumours. Dr Armando del Río Hernández Department of Bioengineering

For the second paper, the researchers studied the role of oxygen in pancreatic cancer. The cells within pancreatic tumours are exposed to very little oxygen, for which they’ve developed a protective mechanism: When oxygen levels drop, the cells release molecules called hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF), which help cancer cells survive these conditions.

This paper shows that tamoxifen mechanically inhibits the production of HIFs, leaving the cancer cells vulnerable to low oxygen levels and more likely to die.

Lead author on both papers, Dr del Río Hernández, said: “Cancer research tends to study the genetic influences on specific cancers, whereas our approach focuses on the physical factors in the environment that affect the growth and spread of tumours. By studying the environment rather than the genes involved in one cancer, we can reveal important traits common to all cancers, and help to identify more broad-spectrum treatments.”

Developing new drugs is expensive and takes many years. The authors say repurposing an established cancer drug for a different tumour type could help effective treatments reach patients much more quickly and cheaply.

However, they caution that because their work was conducted on cell

cultures and mouse models, more research is needed before applying the drug to human patients.

Dr del Río Hernández said: “We must first investigate how giving tamoxifen alone or combined with other chemotherapy drugs during long term treatment affects survival and the spread of cancer.

“Our work lays the ground for more animal studies and perhaps human trials to explore using this well established drug to treat pancreatic cancer. Human trials usually take significant amount of time and their results will ultimately dictate if tamoxifen can be used to treat pancreatic cancer and other solid tumours.”

The research was funded by the European Research Council and done in collaboration with researchers from Queen Mary University of London, Osaka University Japan, Helsinki University Finland and RIKEN Center for Integrative Medical Sciences Japan.

Images: Shutterstock

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Caroline Brogan

Communications Division

Franca Davenport

Communications and Public Affairs