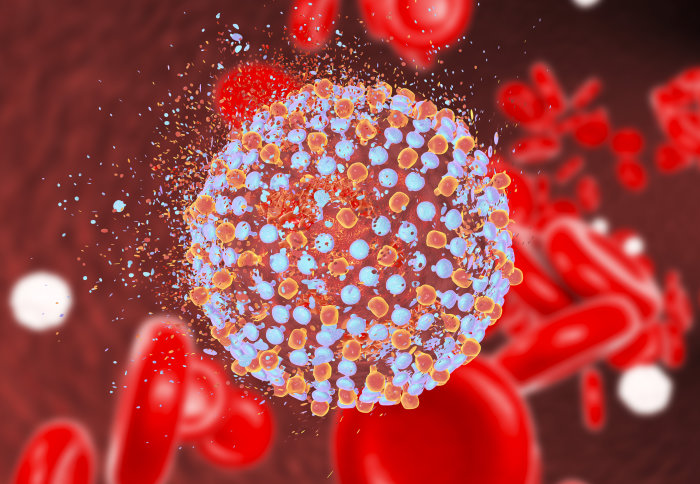

How can we accelerate the elimination of viral hepatitis?

A global panel of experts have published their key recommendations to advance the fight against viral hepatitis.

The Commission, published yesterday in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, assesses the global landscape of the disease, and identifies priorities at a global, regional and national level that are key to its elimination.

Viral hepatitis poses a significant threat to public health and is responsible for an estimated 1.34 million deaths globally every year. In terms of mortality, this places it on a par with other major infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria. The virus exists in several different forms, but the vast majority (96%) of global deaths are caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV). The virus infects and attacks the liver, which can in turn lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Despite presenting a major public health challenge, viral hepatitis has been historically marginalised as a health and development priority. However, in 2015, the UN adopted a resolution calling for specific action to combat viral hepatitis as part of its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which was followed by the publication of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) first global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis in 2016. This newfound, coordinated focus on viral hepatitis means that eliminating the disease is now a realistic goal.

We spoke to lead author Professor Graham Cooke about the Commission in its broader context, and how its proposals can be put into practice.

This report makes a number of recommendations on how we can accelerate the elimination of viral hepatitis. Is there one in particular that you would choose to highlight?

The key thing we have done is to focus on the challenges faced by individual countries. We have defined 20 high-burden countries that are home to over 75% of the burden of disease. Perhaps the most important recommendation is that all of these countries need to have funded national elimination plans by 2020.

Why has it taken until now to acknowledge the significance of viral hepatitis as a global public health threat?

There are a number of reasons for this. Until recently, the burden of viral hepatitis was not well recognised and there were relatively few tools to tackle it. Hepatitis B has an effective vaccine, but we still don’t have one for hepatitis C. In addition, hepatitis C treatment was challenging to take and often ineffective. Recent years have seen great progress in developing treatments for both hepatitis B and C, including therapies better suited to use in low income countries, and this has changed our ambitions for what is possible.

What are the key factors influencing incidence of viral hepatitis on a national or regional basis?

These vary from country to country. In sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, hepatitis B is the greatest challenge, and passing the virus from mother to child will become an increasingly important part of new infection as vaccine coverage improves throughout the world. For hepatitis C, needles used in both healthcare and for recreational drug use remain the major source of new infections.

What opportunities are there within the existing global health infrastructure to facilitate a more coordinated approach to the prevention and treatment of viral hepatitis?

The key challenge is that we need greater investment in tackling viral hepatitis. We have a Global Fund to help fight HIV, TB and malaria, but no such mechanism for viral hepatitis. Ideally, the remit of the global fund could expand, but without it there are other organisations that can help, in particular UNITAID, which has a mandate for improving access to diagnostics and treatment in low income settings

How do you marry the recommendation for “standardised packages of interventions that can be delivered at scale” with the need for context-specific strategies?

If we want to scale up access to prevention and treatment quickly, we need the packages of care to be as simple as possible. However, the realities in each country will be different and the details of how this is best done will need to be tailored to the local setting. International guidelines can provide a template for countries to use for their own national plans.

How will the inclusion of viral hepatitis diagnostics in the WHO’s Essential Diagnostic List (EDL) actually improve the patient journey “on the ground”?

We are increasingly recognising the importance of access to quality diagnostics in the response to infectious diseases as a whole. This was relatively neglected in the early days of the global response to HIV for example, but is now receiving greater attention. Recent years have seen more investment in diagnostics suitable for low income settings, and the EDL will help define the standards for what new diagnostics should look like. By focussing on a smaller number of high priority diagnostics, attention can be focussed on ensuring quality and affordability to those that need them most, by investing in large volume production which can bring prices down.

How can we effectively gather data and monitor progress to ensure countries and regions are on track to meet global targets? What work is being done to correct gaps in baseline data and improve reporting?

While a few countries have good systems for data collection, the majority do not. We don’t really have a good mechanism for tracking progress across countries. Up until now, a lot of data was collated by the Center for Disease Analysis as part of the Polaris Observatory. However, whether this work can continue to be carried out in the long term is unclear.

What are the major factors preventing childhood vaccinations in heavily-burdened countries, and which interventions should be prioritised?

The key issue has been establishing support for the delivery of birth dose hepatitis B vaccine. High levels of vaccination in childhood can prevent over 4 million new infections by 2030, but over 18 million infections could be prevented by high coverage of birth dose vaccine. Until very recently Gavi, the main NGO supporting vaccine delivery in low-income countries, had not prioritised support for birth dose. However, in 2018 they signalled a plan to support wider use that should help to improve access in the poorer countries. There are still practical challenges to delivery, such as the number of births that happen outside health facilities, but innovative solutions, such as vaccine preparations suited to community use, are being developed to tackle these. Beyond vaccination, strengthening maternal health services to ensure timely diagnosis of infected mothers is important to prevent infection of neonates and young children.

Implementing effective harm reduction strategies for high risk groups (such as intravenous drug users and men who have sex with men), can often be bound up in a myriad of complex political and cultural factors. Examples might include national policies on drug use, prison healthcare, and attitudes towards sexual education. How can new prevention strategies begin to navigate these barriers, given that they may involve a huge range of stakeholders and institutions?

Civil society has a key role to play in raising the profile of viral hepatitis and pushing for its inclusion in national policies Professor Graham Cooke Lead author

It is key that policies discriminating against groups at high-risk of infection are removed and that a constructive approach is taken to engaging with those at risk. We see this most strikingly with policies that prevent access to treatment or prevention for those who inject (or even injected) drugs. Decriminalising injecting behaviour and ensuring access to healthcare is essential if viral hepatitis is to be tackled effectively.

What work is currently being done to develop better diagnostic tests for resource-limited settings? Which technologies in development do you think hold the most promise?

There is ongoing research and development work into new tests that might be better suited to low income settings, but no one diagnostic has yet emerged to address all challenges. At the moment, hepatitis is beginning to build on the progress made with improving access to diagnostics for HIV and tuberculosis – for example with the Xpert system. However, these tests remain relatively expensive and difficult to use in primary healthcare settings.

The Commission discusses the possibility of creating “a coalition of stakeholders to create innovative financing for viral hepatitis elimination”. How might this work on a global scale?

Under the banner of the Task Force for Global Health, the WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other partners are developing a coalition that will provide a means to share knowledge and experience, offer technical assistance to overcome barriers, generate new knowledge through research, and report progress toward elimination goals. The Task Force already supports coalitions for several global disease elimination initiatives, and this will extend to viral hepatitis in 2019.

How important is it to increase political engagement in the elimination effort?

Civil society has a key role to play in raising the profile of viral hepatitis and pushing for its inclusion in national policies. Alongside this, health professionals in all countries have a key role in defining the ongoing challenges and arguing for the resources needed to achieve what is possible.

'Accelerating the elimination of viral hepatitis' by Graham S Cooke et al. is published in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology

Lead image: Shutterstock

Article image: Mark Ong, Wikimedia Commons

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ms Genevieve Timmins

Academic Services