Running a hospital in a warzone

Special guest Dr Tom Catena speaks at Imperial on how he saves lives amid oppression, war and conflict.

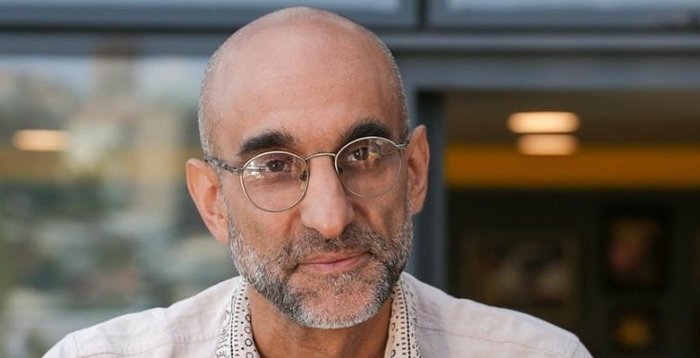

Surgeon, veteran, catholic missionary, globally-recognised humanitarian. These are just some of the badges worn by Dr Tom Catena. So it was with great pleasure and awe that the Institute of Global Health Innovation welcomed Dr Catena to deliver a special lecture on his challenging work, personal life, and lessons for others.

“Tom represents someone who has developed a magnetic capability of inspiring others,” said the College’s Chair of Global Health Dr David Nabarro during his introduction. “He is someone I admire.”

This admiration is shared by many, a fact exemplified back in 2017 when he was awarded the $1.1 million Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity, which recognises unsung heroes whose life-saving work comes at great risk to themselves. Then, in 2018 the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative was proud to appoint Dr Catena as its inaugural Chair. Such admiration rapidly diffused through the room as Dr Catena shared his stories of risk and compassion during his talk at the College, weaving these into a captivating discussion conveyed in a style far from that of a typical lecture.

Love, patience and determination

Dr Catena, or Dr Tom as he is affectionately known by many, opened with his unconventional journey to becoming a doctor, routed through a degree in mechanical engineering and an epiphany at his great aunt’s funeral before arriving at medicine.

“I realised I love sciences, and that I want to help people,” he said. “So I thought: ‘This is what I should do.’”

And on that note, Dr Catena shared some sound advice to students wishing to follow in his footsteps. “Ask yourself: ‘What appeals to you, what attracts you? What do you really love?’ Start with that, and fit things in your life around this. Don’t rush into things, but follow what you feel, step by step. With time, things will come up.”

While patience may sound like a frustrating game, it’s a skill that Dr Catena quickly learned to master.

After his medical training and residency, Dr Catena spent some six years as a volunteer at St Mary’s Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Dr Catena then moved to Sudan where, in 2008, he co-founded the Mother of Mercy Catholic Hospital in the country’s war-struck Nuba Mountains. It took six years to build. And today, he remains the only surgeon permanently based in this region – the size of Austria. But at first he wasn’t welcomed with open arms.

“I was shocked when I arrived and was met with tension and a lot of anger,” he said. “The people had been put down and oppressed, they didn’t trust anyone. I was demoralised, but determined to push ahead.” To build trust, “you need to show people you’re going to stick around, through the good times and bad”. With this attitude, some three years later Dr Catena began to win some credibility among the people.

Building capacity and community

Faced with structural challenges presented by a “poorly-designed disaster” of a building, and air strikes that force him to shelter in the dirt, Dr Catena still manages to regularly treat some 400 people a day. When asked how, he responded with “the buzzword ‘capacity building’”.

“When I started we had 15 Nuba staff who couldn’t do anything; not even weigh a patient, or take their blood pressure. And we had people coming in with their arms blown off. So we spent a long time training them on the job. Now, one of our best anaesthetists is one of those people.

“The only way to keep things going is to train local staff. In the end you have to leave yourself behind. I want 100 Dr Toms there when I leave, who can do what I do but even better.”

Such tenacious, dangerous and selfless work is the true crux of the Aurora Humanitarian Initiative.

“Our collective interest, mine and that of Aurora, is to find more examples of this kind of real, quality, human-centred healthcare,” Dr Nabarro remarked as he closed the lecture.

“It’s demonstrating true humanitarian action.”

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Justine Alford

Institute of Global Health Innovation