How Cassini changed our view of Saturn and its moons

The legacy of the Cassini mission to Saturn was presented by Professor Michele Dougherty at this year’s annual Schrödinger lecture.

Professor Dougherty, Imperial’s Head of Department of Physics, worked with the Cassini mission during its 13 years spent exploring Saturn and its moons. In this special lecture, which you can view in full in the video above, she shared some of the amazing discoveries the mission made and what it was like to work on such a long-lived mission.

From Galileo to Cassini

Professor Dougherty’s first view of Saturn, through her father’s hand-made telescope, was similar to the one Galileo got in 1610 – a hazy planet with some strange bulges out to the side. By the time the Cassini mission reached Saturn in 2004, scientists knew the bulges were distinct rings alongside numerous small moons.

Over the next 13 years, their picture became far clearer, including unprecedented views of the surface of the largest moon Titan, clues as to how the rings were formed, and even data on what the inside of the planet itself might look like.

One instrument on the spacecraft was built at Imperial and managed by Professor Dougherty and her team in the Department of Physics: the magnetometer. This piece of kit, which measured the magnetic field of the planet, was instrumental in making one of the most amazing discoveries of the mission, at the small moon of Enceladus.

Professor Dougherty explained how anomalies in the magnetic data around the moon led her to convince the mission managers to take a closer look – skimming just 173km above the moon. There they discovered enormous plumes of water gas erupting from cracks along the south pole of the moon.

Unlocking Enceladus

As well as likely being the source of Saturn’s outermost ring, the plumes suggested a water ocean beneath it’s the moon’s icy surface. Further investigations revealed a heat source and complex organic materials – some of the essential ingredients for life. Enceladus, and moons like it, are now some of the primary targets for finding life in the solar system and there is hope a new mission could visit Enceladus in the future with this goal in mind.

Cassini ended its mission by breaking up in the atmosphere of Saturn in September 2017, but not before it took a series of daring dives between the inner ring and the planet itself. This last data is still being investigated, and so far has raised more questions, including how the planet sustains a magnetic field.

As the data is analysed, Professor Dougherty already has her eye on the next mission. The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) is due to launch in 2022 with another Imperial-built magnetometer onboard.

Schrödinger scholars

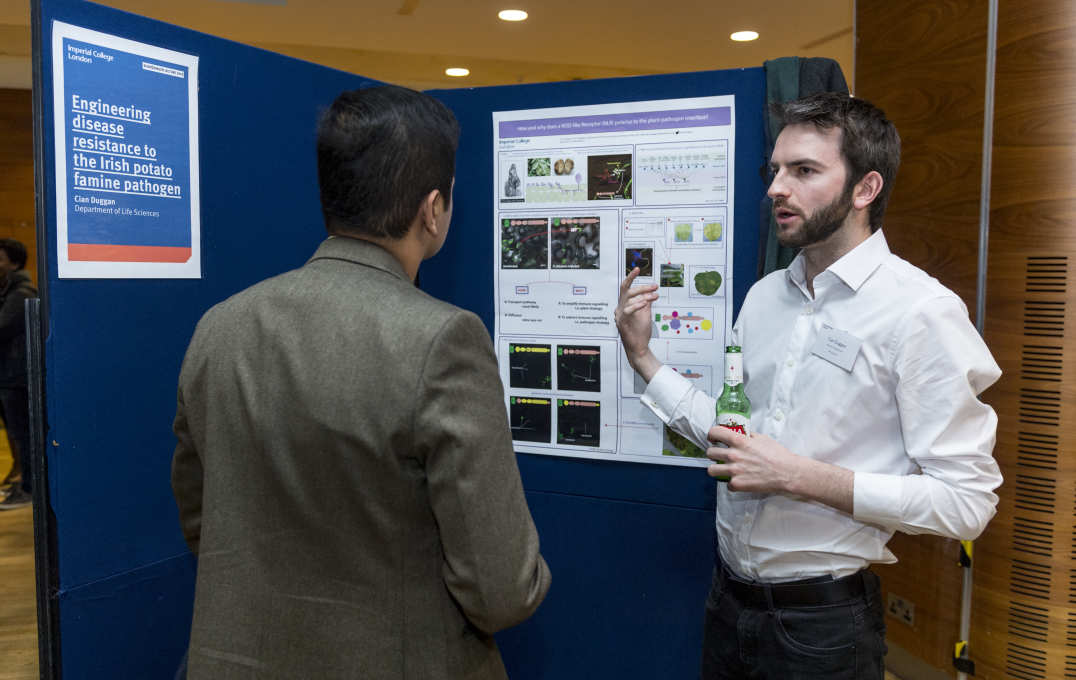

As well as an annual lecture, the Faculty of Natural Sciences awards Schrödinger Scholarships to the most outstanding students who have made an application for admission to study for a full-time PhD in the Departments of Chemistry, Life Sciences, Mathematics and Physics.

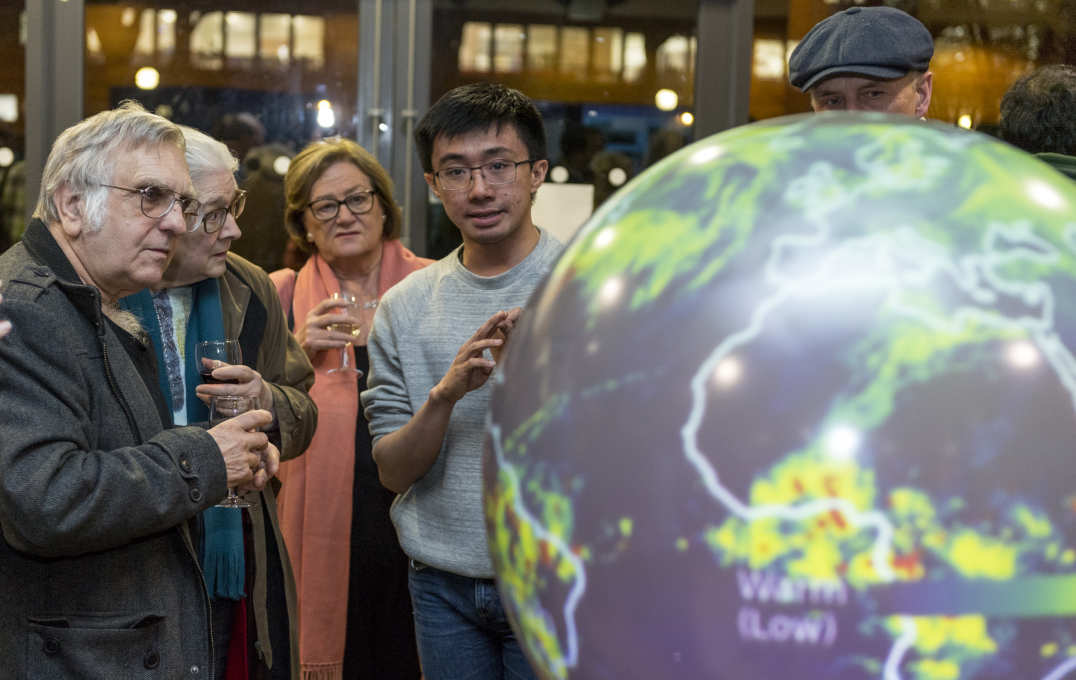

The current scholars displayed their work and chatted to audience members at a reception following the lecture, where Imperial space researchers also demonstrated their latest work.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division