10 questions about blockchain

What is blockchain, where is it used, and will it become mainstream?

These are just some of the questions on the lips of the public as the word – and cryptocurrency in general – are becoming more widely used.

But if you’re new to the idea of blockchain, it can seem a tricky concept to get your head around. With this in mind, we recently sat down with Dr Ying-Ying Hsieh, Assistant Professor of Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Imperial College Business School, to talk about blockchain and its applications in cryptocurrency and beyond.

Here are her confusion-busting answers to some of the public’s most common questions.

1. What is blockchain?

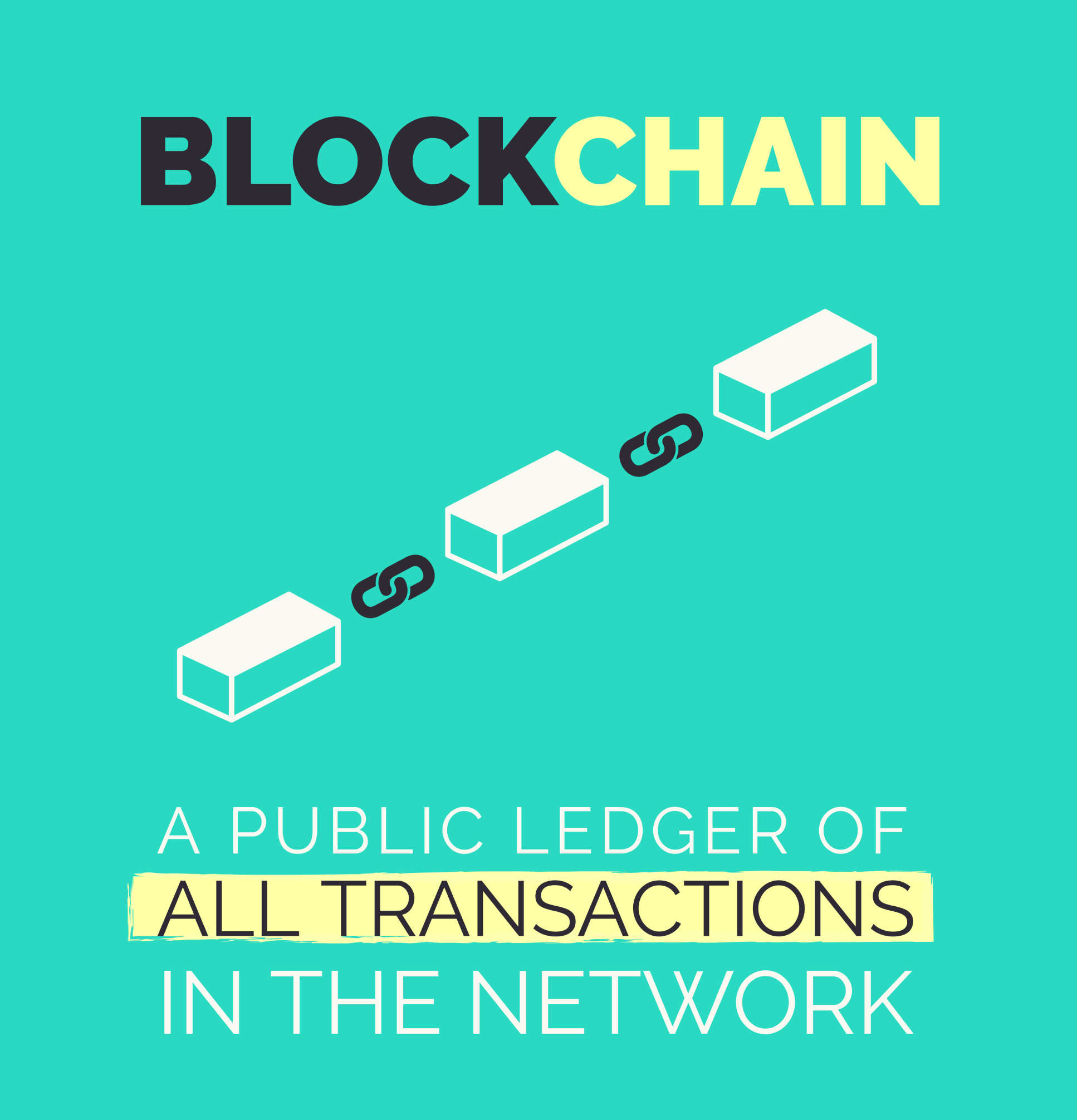

Blockchain is simply a software-powered public ledger that enables the sharing of value, such as payments, between peers online. Importantly, blockchain allows the information to be shared without the need to go through any third-party intermediaries such as banks or payment companies. As its name suggests, it is made of blocks that are connected in chains and each block stores a small part of the history of the transactions that have taken places on the blockchain.

2. When was blockchain first created?

Blockchain is not so much an original idea as it is a combination of a number of pre-existing technologies such as cryptography, peer-to-peer computing and others. The successful first digital implementation of blockchain was in 2008, with the publication of a whitepaper by an anonymous developer, nicknamed Satoshi Nakamoto, in which the idea of blockchain-mediated cryptocurrency, known as bitcoin, was first proposed.

3. How does blockchain support bitcoin?

Bitcoin is a cryptocurrency that one can think of as digital cash. Bitcoin only exists online and therefore, its exchange needs to be recorded digitally. Blockchain essentially acts as a digital ledger to record all transactions happening between the peers online and provides a secure and decentralised record for all of the exchanges.

4. What does a decentralised blockchain mean?

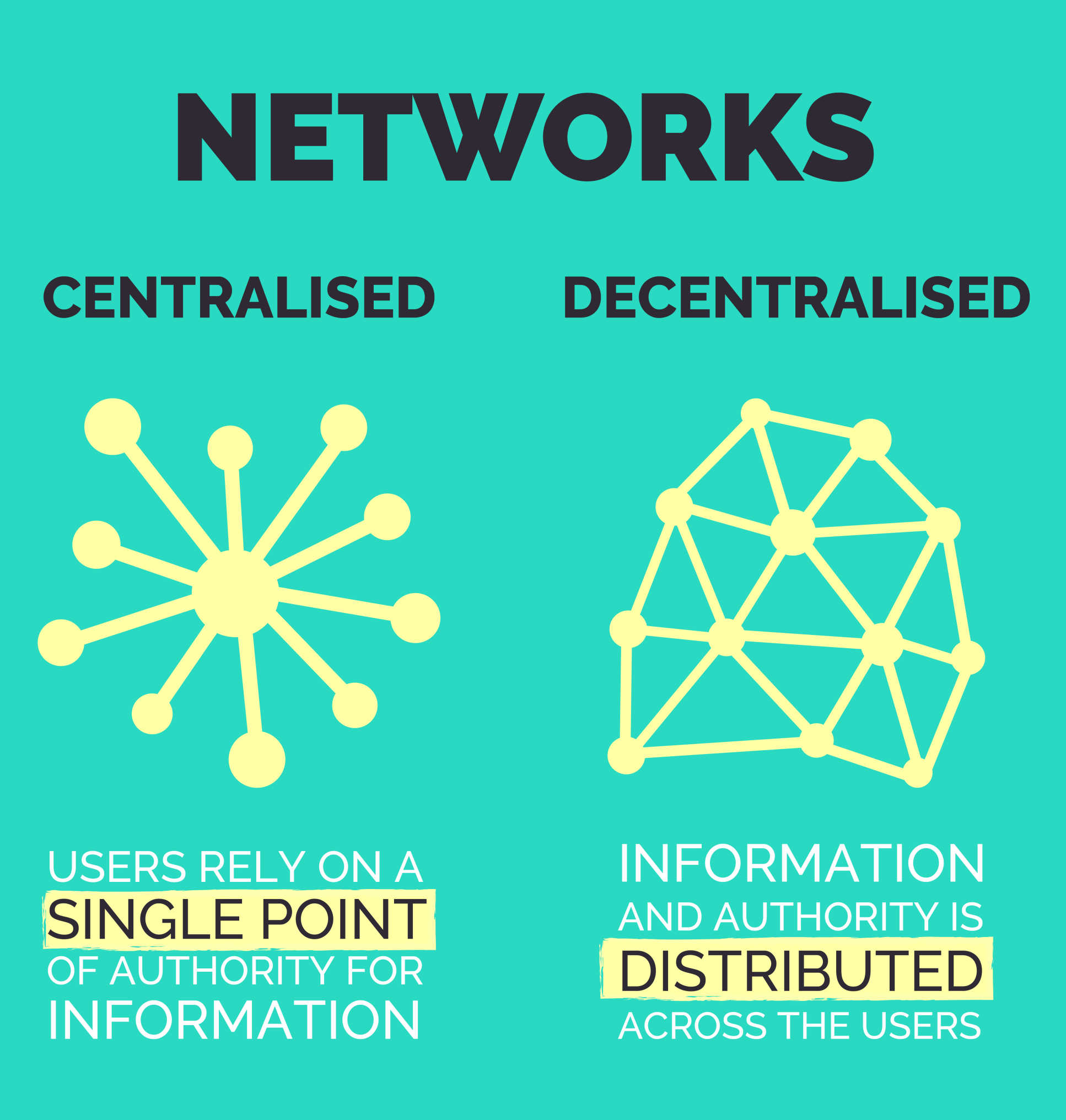

It means that the information in the blockchain is not stored in a single place but it is distributed across the network of people who are using it. For example, standard cash, such as pounds or dollars, are issued by the central banks that keep the records of where the money is going. However, with bitcoin, there is no single entity that is responsible for issuing bitcoins and keeping the records. Bitcoin works through an anonymous network of people who provide nodes to the blockchain. Anyone can join or exit the blockchain at any time and the cross-validation between the nodes is required to record anything on the ledger.

5. Does the decentralised nature of the blockchain make it more secure?

Yes, here is an example: if you have a pot of gold you can store it in the vault and trust the people who own the vault, i.e. banks and their personnel, to keep it safe for you. But if your gold is analogous to bitcoin, then, rather than putting your pot of gold into a bank vault, you actually put it in someone’s house in some imaginary village and it gets moved to a new house every 10 minutes or so. No one knows where your gold will be moved, which makes it very difficult for any burglar to know where it will be at any given time. Moreover, to enter the houses in which your gold is stored, the burglar would need to solve complicated equations, which are both time consuming and extremely energy expensive.

6. But there have been many reports of bitcoins being stolen, so it is possible to hack the blockchain, right?

Well, most of those reports actually refer to the hacking of exchanges in which the cryptocurrencies are being traded and not the blockchain itself. In fact, we can still find the stolen currency on the blockchain we just do not have the access to it or know who has stolen it.

7. Can anyone start a blockchain?

Yes, in principle anyone with some computing knowledge can do it, but the start is the easy part. The success and value of the blockchain comes from its size and to make it attractive to the users the creator of the new blockchain needs to be able to grow it fast by adding as many blocks as possible to the chain. The scaling of the blockchain is referred to as bootstrapping and it is often done through the so-called initial coin offerings at the early stages of a cryptocurrency creation.

8. Are there different types of blockchains?

Currently there are several different types of blockchains, which were mostly developed to improve the original bitcoin blockchain. Another very popular blockchain is the Ethereum blockchain developed to exchange ether tokens online. Ethereum blockchain is more energy efficient, allows smart contracts (transfer of currency only under certain conditions) and also uses proof-of-stake rather than proof-of-work protocols to validate transactions.

9. Is there any disadvantage to using a blockchain?

Perhaps the biggest disadvantage from the government’s perspective is that blockchain-based technologies are very difficult to track. The decentralised nature of the blockchain makes it difficult to regulate transactions happening online and therefore, it is very attractive for criminals to use it for illegal trade and money laundering purposes. In fact, we often see bitcoins being the preferred payment method during the ransomware attacks and in online black market for weapons and drugs.

10. Can blockchain be used outside the cryptocurrency field?

There are many potential avenues for the use of blockchain, though, so far, it has been used more as a proof-of-concept and not yet fully implemented. Essentially, any situation where trust is of key importance could make use of blockchain, whether that is the financial industry or electronic voting systems. In the shipping industry the blockchain could be used to track where the goods versus the money is, and in the healthcare system it could be used for the secure storage of patient data.

Listen to Bernadeta’s interview with Dr Ying-Ying Hsieh:

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Bernadeta Dadonaite

Centre for Languages, Culture and Communication