Researchers identify a new way to target treatment-resistant cancers

An international team of researchers has found a different way cancer becomes resistant to chemotherapy, suggesting a new target for drugs.

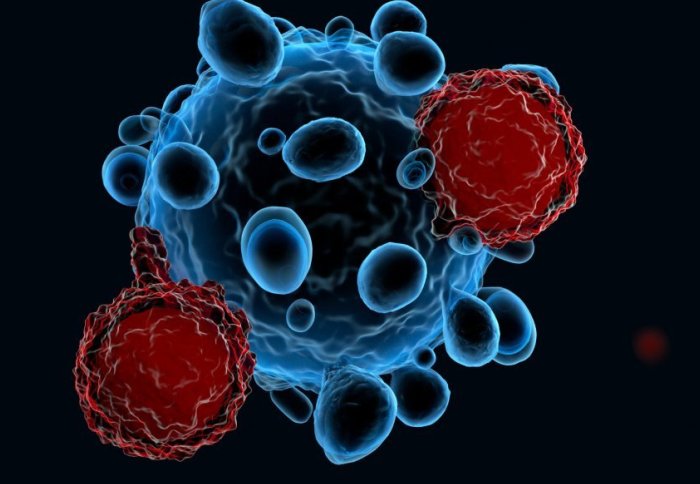

Chemotherapy kills cancers cells by preventing them from multiplying and by inducing ‘cell death’, a natural process that can be enhanced with drugs. One form of cell death, called ferroptosis – iron-dependent cell death – is caused by the degradation of fats (lipids) that make up the cell membrane.

Discovering a completely new way cells gain resistance will allow us to design drugs that target this mechanism. Professor Ed Tate

Now, a team led by researchers from Germany and including Imperial College London scientists have discovered a new mechanism by which cancer cells become resistant to ferroptosis. Many aggressive and drug-resistant cancers are vulnerable to ferroptosis but they can also use particular mechanisms to block it.

The team’s work, published today in Nature, provides a new target for drugs that suppress the newly discovered mechanism, allowing ferroptosis cell death to take hold in susceptible cancer cells.

Professor Ed Tate, from the Department of Chemistry at Imperial, said: “Discovering a completely new way cells gain resistance will allow us to design drugs that target this mechanism. In fact, we already have drug leads we previously developed that indirectly target this mechanism, and are testing them in the lab.”

Reducing resistance

Ferroptosis relies on oxidation on lipids in the cell membrane – the stripping of electrons from these lipids, causing them to degrade. It was already known that one molecule, called glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), reverses this process, acting as an antioxidant.

There are drugs that target GPX4, but most cancers are still resistant to ferroptosis.

Now, the research team discovered a different molecule called FSP1 that also acts as a lipid antioxidant, rescuing cancer cells from ferroptosis cell death even when they are starved of GPX4.

As well as identifying FSP1's role in preventing ferroptosis, the team also found several potential ways to target it with drugs and therefore reduce resistance.

Great potential for clinical applications

To work, FSP1 needs the help of an enzyme called N-myristoyltransferase, or NMT. Previously, the team at Imperial developed drug leads for suppressing the activity of NMT in order to block infection by the common cold virus.

Andrea Goya Grocin, a CRUK-funded PhD student in the group of Professor Tate in the Department of Chemistry, applied a suite of chemical tools developed at Imperial to study FSP1 and its modification by NMT.

Andrea said: “As therapy-resistant tumours gain resistance to ferroptosis, treatments that promote ferroptosis based on inhibition of FSP1, GPX4, NMT, or a combination of all three, have great potential for translation into future clinical applications.”

This research illustrates the importance of transnational and European collaboration, with key contributions from Helmholtz Zentrum München, University of Würzburg, Cardiff University, University of Ottawa, Imperial College London and the University of California, Berkeley, funded by organisations in Germany, the European Research Council, and Cancer Research UK (Programme Foundation Award to Professor Tate, with support from the Imperial College CRUK Centre and the EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Chemical Biology).

-

‘FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor’ by Doll et al. is published in Nature.

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division