Solar storms could be more extreme if they ‘slipstream’ behind each other

Modelling of an extreme space weather event that narrowly missed Earth in 2012 shows it could have been even worse if paired with another event.

The findings suggest space weather predictions should be updated to include how close events enhance one another.

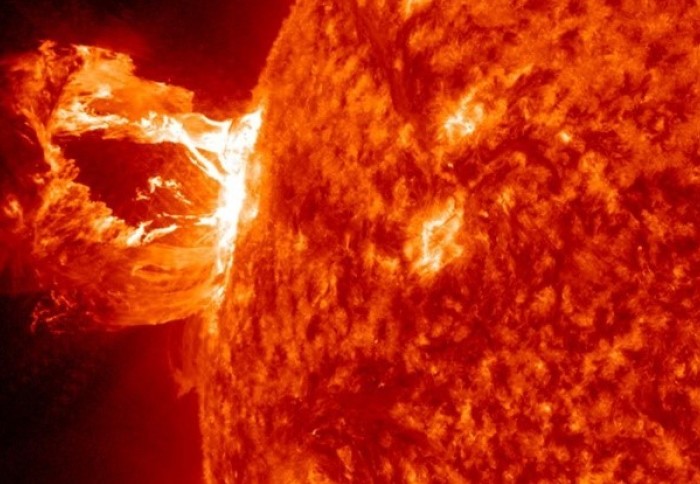

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are eruptions of vast amounts of magnetised material from the Sun that travel at high speeds, releasing a huge amount of energy in a short time. When they reach Earth, these solar storms trigger amazing auroral displays, but can disrupt power grids, satellites and communications.

The 23 July 2012 event is widely regarded as the most extreme space weather event of the space age, and if this event had struck Earth it could have disrupted the technology we increasingly rely on for our day-to-day lives Dr Ravindra Desai

These most extreme of ‘space weather’ events have the potential to be catastrophic, causing power blackouts that would disable anything plugged into a socket and damage to transformers that could take years to repair. Accurate monitoring and predictions are therefore important to minimising damage.

Now, a research team led by Imperial College London have shown how CMEs could be more extreme than previously thought when two events follow each other. Their results are published today in a special issue of Solar Physics focussing on space weather.

Technological blackouts

The team investigated a large CME that occurred on 23 July 2012 and narrowly missed Earth by a couple of days. The CME was estimated to travel at around 2250 kilometres per second, making it comparable to one of the largest events ever recorded, the so-called Carrington event in 1859. Damage estimates for such an event striking Earth today have run into the trillions of dollars.

Lead author Dr Ravindra Desai, from the Department of Physics at Imperial, said: “The 23 July 2012 event is widely regarded as the most extreme space weather event of the space age, and if this event had struck Earth it could have disrupted the technology we increasingly rely on for our day-to-day lives. We find however that this event could actually have been even faster and more intense if it had been launched several days earlier directly behind another event.”

To determine what made the CME so extreme, the team investigated one of the possible causes: the release of another CME on the 19 July 2012, just a few days before. It has been suggested that one CME can ‘clear the way’ for another.

CMEs travel faster than the ambient solar wind, the stream of charged particles constantly flowing from the Sun. This means the solar wind exerts drag on the travelling CME, slowing it down.

However, if a previous CME has recently passed through, the solar wind will be affected in such a way that it will not slow down the subsequent CME as much. This is similar to how race car drivers ‘slipstream’ behind one another to gain a speed advantage.

Magnifying extreme space weather events

The team created a model that accurately represented the characteristics of the 23 July event and then simulated what would happen if it had occurred earlier or later – i.e. closer to or further from the 19 July event.

Our model results can contribute to current space weather forecasting efforts. Han Zhang

They found that by the time of the 23 July event the solar wind had largely recovered from the 19 July event, so the previous event had little impact. However, their model showed that if the latter CME had occurred earlier, closer to the 19 July event, then it would have been even more extreme – perhaps reaching speeds of up to 2750 kilometres per second or more.

Han Zhang, co-author and student who worked on the development of this modelling capability, said: “We show that the phenomenon of 'solar wind preconditioning', where an initial CME causes a subsequent CME to travel faster, is important for magnifying extreme space weather events. Our model results, showing the magnitude of the effect and how long the effect lasts, can contribute to current space weather forecasting efforts.”

The Sun is now entering its next 11-year cycle of increasing activity, which brings increased chances of Earth-bound solar storms. Emma Davies, co-author and PhD student supported by the Science and Technology Facilities Council said: “There have been previous instances of successive solar storms bombarding the Earth, such as the Halloween Storms of 2003. During this period, the Sun produced many solar flares, with accompanying CMEs of speeds around 2000 km/s.

"These events damaged satellites and communication systems, caused aircraft to be re-routed, and a power outage in Sweden. There is always the possibility of similar or worse scenarios occurring this next solar cycle, therefore accurate models for prediction are vital to help mitigate their effects.”

The research was funded in part by the Science and Technology Facilities Council.

-

‘Three Dimensional Simulations of Solar Wind Preconditioning and the 23 July 2012 Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection’ by Ravindra Desai, Han Zhang, Emma Davies, Julia Stawarz, Joan Mico-Gomez and Pilar Iváñez-Ballesteros is published in Solar Physics.

Top image: A previous CME observed by Nasa's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO)

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division