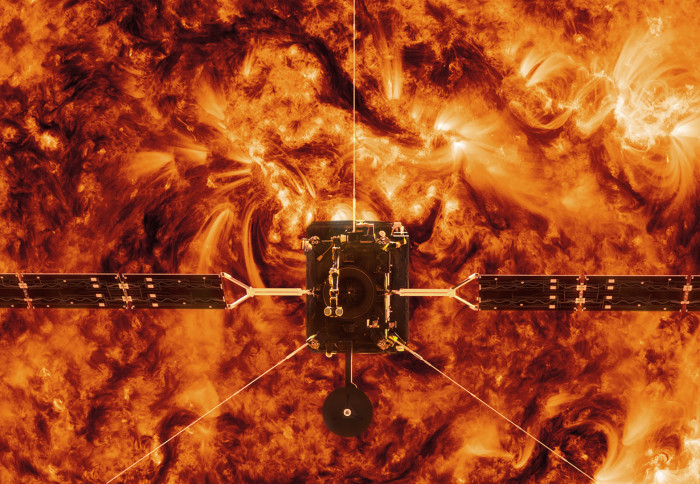

Solar Orbiter’s first science data shows the Sun at its quietest

Three of the Solar Orbiter spacecraft’s instruments, including Imperial’s magnetometer, have released their first data.

The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter spacecraft launched in February 2020 on its mission to study to Sun and began collecting science data in June. Now, three of its ten instruments have released their first tranche of data, revealing the state of the Sun in a ‘quiet’ phase.

Solar Orbiter is living up to its promise. We always knew it was going to be a fantastic mission and the early measurements are showing just how much potential there is for unprecedented insights into the Sun. Professor Tim Horbury

The Sun is known to follow an 11-year cycle of sunspot activity and is currently almost completely free of sunspots. This is expected to change over the coming years as sunspot activity ramps up, causing the Sun to become more active and raising the chances of adverse ‘space weather’ events, where the Sun releases huge amounts of material and energy in solar flares and coronal mass ejections.

The Sun’s activity is closely linked to the state of its magnetic field, and this is measured by Imperial’s instrument aboard Solar Orbiter, the magnetometer (MAG). Since June, MAG has recorded hundreds of millions of ‘vectors’ – measurements of the direction and strength of the Sun’s magnetic field.

Solar Orbiter has already flown inside the orbit of Venus, collecting some of the closest data to the Sun so far, and will get progressively closer in the coming years. It is currently orbiting close to the equator of the Sun, which in times of high activity would show a very warped magnetic field.

Currently, however, the Sun’s magnetic ‘equator’ is lying very flat to the true equator, allowing the spacecraft to observe fields from the Northern magnetic hemisphere for weeks on end, when just a few degrees north of the equator. Near times of high solar activity, when the Sun’s magnetic equator is more warped, it is not possible to see a single polarity of magnetic field for so long.

Solar wind structure

The MAG has also observed waves caused by protons and electrons streaming from the Sun. Further out, near the Earth, these particles are distributed more evenly in the bulk solar wind of charged particles streaming from the Sun, but at Solar Orbiter there are also ‘beams’ of protons and electrons coming from the Sun.

There appears to much more structure in the solar wind closer to the Sun, and this is further shown by MAG confirming the presence of ‘switchbacks’ – dramatic folds in the solar wind first recorded by the Parker Solar Probe, a NASA mission launched in 2018.

Solar Orbiter and the Parker Solar Probe will work together over the coming years to compare data on the same phenomena at different distances and orbits around the Sun as it wakes up and enters the next phase of its sunspot cycle.

A testament to hard work

The data released today are part of Solar Orbiter’s commitment to releasing data within three months of it arriving on the ground – a tight schedule for any space mission, but particularly challenging during a pandemic. Professor Tim Horbury, the Principal Investigator for MAG from the Department of Physics at Imperial, says that the fact the data is ready on time is testament to the hard work of the engineering team at Imperial.

“They have worked incredibly hard over the last few months. It’s been an immense amount of work,” he said. But it’s paid off. “There's a lot of it that we're releasing that nobody's really looked at in great detail yet. So I am sure there will also be a whole extra set of wonders – we just don't know what they are yet. There's an enormous amount for people to do, and I really hope that people will dive in.”

MAG has been performing brilliantly for seven months now. We tested it here on Earth before launch, but we cannot perfectly recreate the harsh space environment, and certainly not for the prolonged periods MAG is now experiencing. Helen O'Brien

One of the first challenges from the team was to eliminate the tiny magnetic field signatures from the spacecraft itself. Almost everything that runs on electrical power on the spacecraft creates a varying magnetic field that must be removed from the data in order to get the true signal from the Sun. This includes the solar panels, the thrusters, the other science instruments and over 50 separate heaters.

While different parts of the spacecraft turned on, the team had to take data from all of them in order to eliminate their signal. But Professor Horbury says it was all worth it: “This is just the beginning, but the data is already enormously exciting and very rich.

“Solar Orbiter is living up to its promise. We always knew it was going to be a fantastic mission and the early measurements are showing just how much potential there is for unprecedented insights into the Sun,” he said.

MAG Instrument Manager Helen O’Brien said: “MAG has been performing brilliantly for seven months now. We tested it here on Earth before launch, but we cannot perfectly recreate the harsh space environment, and certainly not for the prolonged periods MAG is now experiencing.

“So to see the first data go public is wonderful, and this is just the beginning. In December, the spacecraft does a flyby of Venus, and then we are back in to half the Sun-Earth distance in February next year. We are so proud!”

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division