Hole-punching bacteria could be engineered to attack pathogens

Researchers have discovered how to engineer bacteria that normally attack human cells so that they kill other pathogens instead.

Many pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria use specific proteins to punch holes in the cell membranes of their hosts, killing them.

Now, researchers from Imperial College London and University College London have determined exactly how they do this and have discovered a way to change the type of cell that is attacked.

This has the potential to turn the tables on pathogens and increase our arsenal to fight them. Dr Doryen Bubeck

The research, published today in Nature Communications, provides a blueprint for repurposing these hole-punching bacteria to kill other targets, such as pathogens that infect plants.

Lead researcher Dr Doryen Bubeck, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: “Using state-of-the art imaging techniques, we have caught these bacterial nanomachines in the act of making a hole.

“We have discovered how this process can be engineered and redirected, potentially to our benefit, to attack new kinds of cells. This has the potential to turn the tables on pathogens and increase our arsenal to fight them.”

Caught in the act

The proteins used by many pathogenic bacteria to punch holes in cell membranes are called cholesterol-dependent cytolysins (CDCs). Cholesterol is a lipid, which is a fatty molecule that human cells use to build their membranes. Scientists knew CDCs used the cholesterol in cell membranes to form the holes that ultimately rupture the cells, but they didn’t know exactly how.

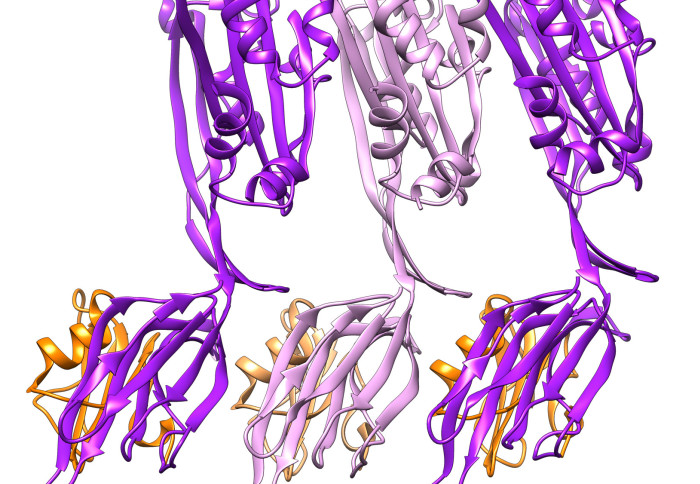

The team was able to stall CDCs in the act of forming the hole and imaged them in high detail using a technique called cryo-electron microscopy. They found that during a crucial phase at the start of the hole-forming process the CDCs change their shape so that many proteins can come together side-by-side on the membrane to form a ring. One of these changes involved the movement of a horizontal helix structure.

They also found that by engineering the bacteria to tweak the properties of this helix they could remove the CDC’s dependence on cholesterol. The pathogenic bacteria themselves have no cholesterol, which they may have evolved as a way to protect themselves from their own hole-punching proteins. Removing the dependence on cholesterol therefore opens up the possibility of attacking other types of pathogenic bacteria.

Hole-punching nanomachines

First author Dr Nita Shah, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial, said: “What’s really exciting is that this special helix used by CDCs is also found in many other types of proteins – not only in pathogenic bacteria, but also as part of our own immune system. So, the clues we’ve uncovered in this study could be applied to tune a variety of hole-punching nanomachines.”

The team is now using the same technique to investigate other interactions between pathogenic bacteria and host cells. Some CDCs attach to cell membranes by ‘hijacking’ an immune receptor on the surface of the membrane, so the team is looking into related proteins that hijack other receptors to discover other ways in which the process may be manipulated.

-

‘Structural basis for tuning activity and membrane specificity of bacterial cytolysins’ by Nita R. Shah, Tomas B. Voisin, Edward S. Parsons, Courtney M. Boyd, Bart W. Hoogenboom and Doryen Bubeck is published in Nature Communications.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division