Heart damage found in half of COVID-19 patients discharged after hospitalisation

by Maxine Myers

Half of patients who have been hospitalised with severe COVID-19 have damage to their hearts.

Half of patients who have been hospitalised with severe COVID-19 have damage to their hearts.

The damage includes inflammation of the heart muscle (myocarditis), scarring or death of heart tissue (infarction), restricted blood supply to the heart (ischaemia) and combinations of all three.

The study, published in the European Heart Journal, involves 148 patients from six hospitals in London and led by scientists at Imperial College London and University College London (UCL).

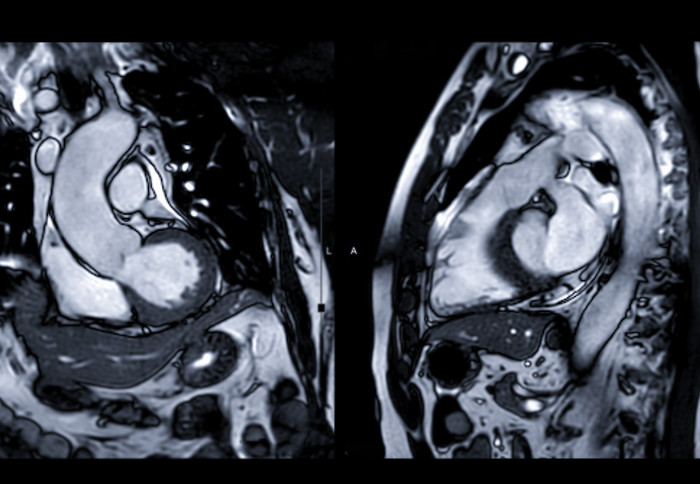

The team carried out MRI scans on patients who had been admitted to hospital and had elevation of a protein in the blood called troponin.

COVID-19 heart complications

Dr Graham Cole lead author of the study from the National Heart and Lung Institute at Imperial College London and Consultant Cardiologist at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, said: "These findings have confirmed further complications and outcomes for hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19. Many of these patients have underlying health conditions and may experience further problems after recovering from COVID-19. The study shows that MRI scans of the heart are useful in patients with COVID-19 whose troponin was raised.”

Troponin is released into the bloodstream after a heart attack. Raised levels can occur when an artery becomes blocked or there is inflammation of the heart. Many patients who are hospitalised with COVID-19 have raised troponin levels during the critical illness phase, when the body mounts an exaggerated immune response to the infection.

Patients who develop severe COVID-19 disease often have pre-existing heart-related health problems including diabetes, raised blood pressure and obesity. The researchers wanted to see if the heart was directly affected by severe COVID-19.

The team analysed 148 COVID-19 patients discharged up until June 2020 from six hospitals across three NHS London trusts: Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust and University College London Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Patients who had abnormal troponin levels were offered an MRI scan of the heart a month or two after discharge to see if there was any damage to the heart. The results were compared with those from a control group of patients who had not had COVID-19 but were matched for age and other comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes, as well as from 40 healthy volunteers.

Heart damage

The researchers found evidence of heart muscle injury that could be seen on the scans a month or two after discharge. The function of the heart’s left ventricle, the chamber that is responsible for pumping oxygenated blood to all parts of the body, was normal in 131 of the 148 patients but scarring, injury to the heart muscle or problems with the heart’s blood supply was present in 80 patients. The pattern of tissue scarring, or injury originated from inflammation in 39 patients, from ischaemic heart disease, which includes infarction or ischaemia, in 32 patients, and from both in nine patients. Twelve patients appeared to have ongoing heart inflammation.

Although some of the heart damage may have been pre-existing, the researchers suggest that some of the damage was new and likely caused by COVID-19. In the most severe cases, there are concerns that this injury may increase the risks of heart failure in the future, but more work is needed to investigate this further.

Further work

The researchers also suggest that the findings from the study could be used to identify patients at higher or lower risk and suggest potential strategies that may improve outcomes.

The findings from the study only included patients who survived a coronavirus infection that required hospital stays. The team believe that more work needs to be done to explore the impact of COVID-19 on patients who had COVID-19 but were not hospitalised and those who are hospitalised but without elevated troponin to see if COVID-19 has an impact on long-term heart health.

The study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR).

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Maxine Myers

Communications Division