New study reveals weak spots in chemotherapy-resistant cancer cells

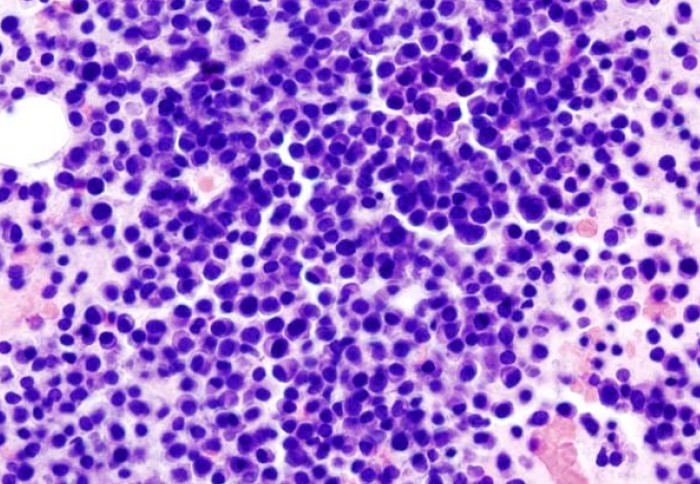

Multiple myeloma is a form of cancer that develops in the bone marrow

Molecular ‘weak spots' in cancer cells recovering from chemotherapy could provide the basis for better treatments, according to new research

Chemotherapy sometimes fails to cure patients because a proportion of cancer cells resist its toxic effects. However, how these cells bounce back from the ‘stress’ caused by chemotherapy is not well understood.

To gain insights into the recovery process, scientists based at the Hugh and Josseline Langmuir Centre for Myeloma Research developed a lab-based model to observe the different molecular events taking place within stressed myeloma cells – an incurable form of bone marrow cancer.

The findings, published in the journal PNAS, reveal that these recovering cells show specific vulnerabilities which could be exploited to improve cancer therapies.

Cellular ‘trade-offs’

Cancer cells are uniquely resilient because of their ability to rapidly adapt to challenges in their environment. However, in diverting their resources to tackle specific threats, cells may need to make certain ‘trade-offs’, leaving them susceptible to other challenges. Understanding these weak spots could therefore help scientists to identify new targets for treatments and enhance existing therapies.

On this basis, Imperial researchers set out to gain a better understanding of how cancer cells recover from chemotherapy-induced stress and the vulnerabilities that this could expose.

To do this, the team created a lab-based model to allow them to observe the molecular events taking place within recovering cells. They exposed myeloma cells to a proteasome inhibitor, a kind of drug commonly used in myeloma treatment, and studied different aspects of cell biology: gene activity, protein levels, metabolism, and the function of the cells' power stations', the mitochondria.

Identifying weak spots

The researchers found that therapy-induced stress triggered unexpectedly complex and protracted changes within the recovering cells. The team also compared their findings to those of a separate, in vivo study to verify the model’s ability to reproduce clinically relevant effects.

The findings indicate that several aspects of mitochondrial function were compromised in recovering cells, highlighting a significant point of vulnerability that could be further targeted.

They also suggest that GCN2 – a specialised enzyme that senses and responds to amino acid deficiency – could be an ‘Achilles’ heel’ for recovering myeloma cells. Moreover, through further analysis, researchers found that GCN2 could be a potential treatment target for a range of other cancers – possibly without prior treatment with other drugs.

Next steps

By identifying the trade-offs made by recovering myeloma cells, the study’s findings represent an important first step in identifying potential new treatment targets and optimising existing cancer therapies.

Lead author Dr Holger Auner, Clinical Reader in Molecular Haemato-Oncology at the Department of Immunology and Inflammation, commented: “We are now exploring the vulnerabilities we found in greater depth to better understand what cancers might be most amenable to drugs targeting these weak spots.”

“We are also collaborating with industry to try and develop a new drug that blocks the function of one of the molecules that helps myeloma cells recover from proteasome inhibitors.”

First author Paula Saavedra-Garcia, Research Associate at the Department of Immunology and Inflammation, added: "I am very excited about the work as it highlights the importance of metabolism in cancer, and how metabolic vulnerabilities may provide new avenues for optimising cancer therapies."

‘Systems level profiling of chemotherapy-induced stress resolution in cancer cells reveals druggable trade-offs’ by Paula Saavedra-Garcia et al. is published in PNAS

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ms Genevieve Timmins

Academic Services