10 Imperial moments that were out of this world in 2021

by Jacklin Kwan

From uncovering what killed the dinosaurs to exploring rocky terrains on Mars, here are 10 moments from 2021 when Imperial took on the final frontier.

While most of us were excited just to get out of the house again, Imperial College London researchers were looking towards the skies.

Perseverance pays off

On 18 February, NASA’s latest rover Perseverance touched down safely on Mars in the 28-mile wide Jezero crater. The robotic explorer is tasked with looking for clues of ancient life in Mars’s geographical terrain and the composition of its soil that could hint towards the planet’s previous habitability.

Imperial researchers are heavily involved in the mission. Their work includes finding promising soil and rock samples for a return to Earth and trialling exciting new technologies that could help future astronauts on their expeditions (such as a method to produce oxygen on Mars).

Professor Mark Sephton, Head of the Department of Earth Science and Engineering who’s an Imperial astrobiologist on the Perseverance mission, said: “This could be the mission that answers the question of whether life ever existed on Mars.”

A gift from above

A rare meteorite – the only one of its kind to ever land in the UK – fell from the sky on 28 February and was recovered by Imperial scientists.

Over 1,000 eyewitnesses saw the meteorite tear through the night sky, which was captured on camera by the UK Fireball Alliance (UKFAII).

Imperial’s contribution to UKFAII was led by Dr Sarah McMullan from the Department of Earth Science and Engineering. Together with her team, she helped to recover fragments of the meteorite, which was composed of carbonaceous chondrite: a class of primitive space rock.

By analysing the fragments, researchers hope to gain information about the birth of life in the early days of the Solar System as well as what planets are made from.

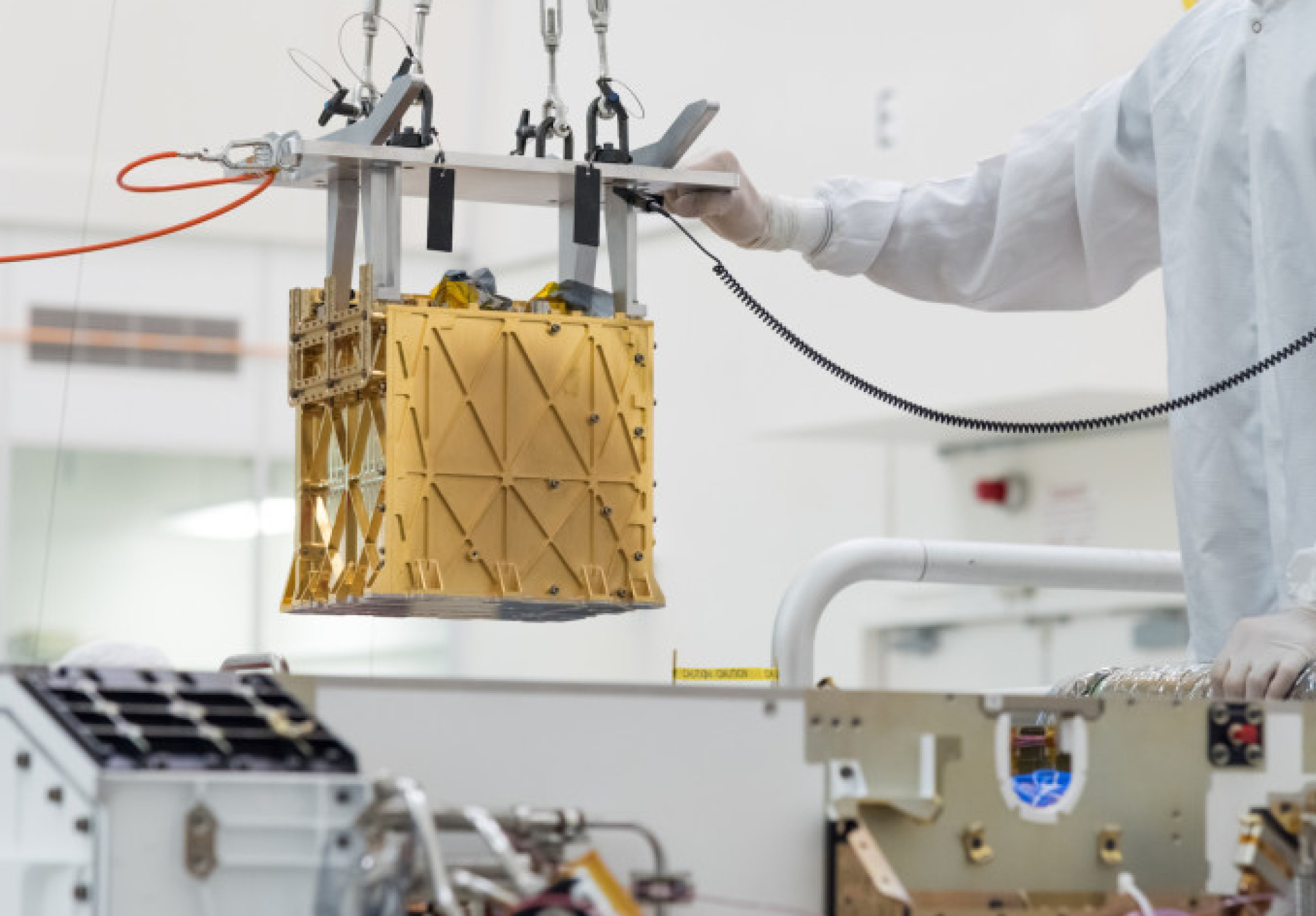

Mars rover shows MOXIE

NASA’s Perseverance rover successfully produced breathable oxygen on Mars for the first time. The Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE) was an experiment to convert carbon dioxide found in the red planet’s atmosphere to oxygen.

Perseverance was able to produce about five grams of oxygen, the equivalent of ten minutes worth of breathable oxygen for an astronaut.

Professor Tom Pike from the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering is a co-investigator on MOXIE and said: “We are moving at pace towards getting the first human on Mars.

“The technology demonstrated by MOXIE could help provide the fuel for such return flights using the resources of Mars itself.”

Ready to leave home and explore Jupiter’s moons

After trying times during COVID, Imperial’s magnetometer is finally ready to set off to study Jupiter’s icy moons. The magnetometer will measure magnetic fields in space as part of the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission, due to launch in August 2022.

Members of Imperial’s Department of Physics were quick to adapt to the pandemic – some parts of the far-flying magnetometer were assembled on the team’s own kitchen tables when they were unable to use the university’s research labs. Researchers even undertook the finnicky work of cleaning sensitive parts of the instrument with cotton buds when they would usually have access to dust-free clean rooms.

What killed the dinosaurs?

Research from the Free University of Brussels-VUB and Imperial argued that space dust found atop the Chicxulub crater was strong evidence that the asteroid which created it caused the mass extinction of dinosaurs.

Scientists analysed a cross section of rock layers recovered from a drilling expedition. They found that there were high iridium levels in the sediment layers that marked the catastrophic end of the Cretaceous Period.

The team believes these iridium levels are explained by the asteroid vaporising upon impact and ejecting iridium in the Earth’s atmosphere where it circled the planet in a dust cloud. This space dust cloud eventually settled, creating a spike in worldwide iridium deposits which are most concentrated at the Chicxulub crater.

Dunes on Mars let us go back in time

NASA’s Curiosity rover helped to uncover ancient sand dunes on Mars by investigating current rock formations on the planet’s surface.

Imperial researchers used Curiosity’s pictures of rock units on Mars which contained clues about the shape and size of these ancient dunes, allowing them to model the wind conditions that created them in the first place.

From these models, the scientists were able look back three and a half billion years ago when two competing winds drove large sand dunes across the Gale crater – the remnants of a dried lakebed.

Rovers have allowed scientists to explore Mars like never before. Lead author Dr Steven Banham said: “Although geologists have been reading rocks on Earth for 200 years, it’s only in the last decade or so that we’ve been able to read Martian rocks with the same level of detail as we do on Earth.”

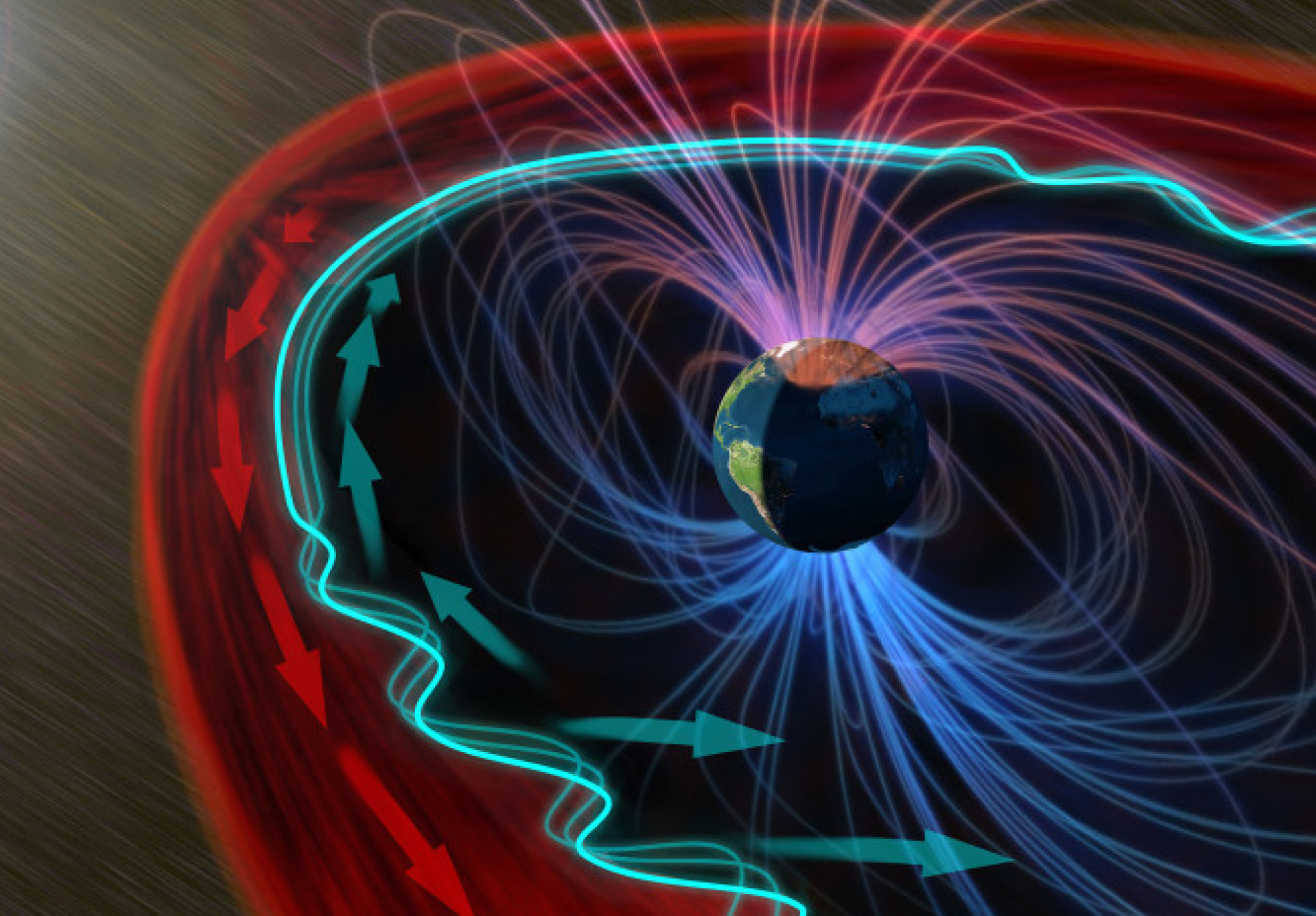

Putting an ear up to solar winds

The magnetic field around Earth protects us from streams of charged particles that are released by the Sun called ‘solar winds.’ At first, researchers thought that Earth’s magnetosphere would ripple after being struck by solar winds, but Imperial researchers used models and observations from NASA satellites to explain why the magnetosphere appears to remain completely still.

Excitingly, researchers also translated the electromagnetic signals from NASA’s THEMIS (Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms) satellites into a soundtrack of solar winds!

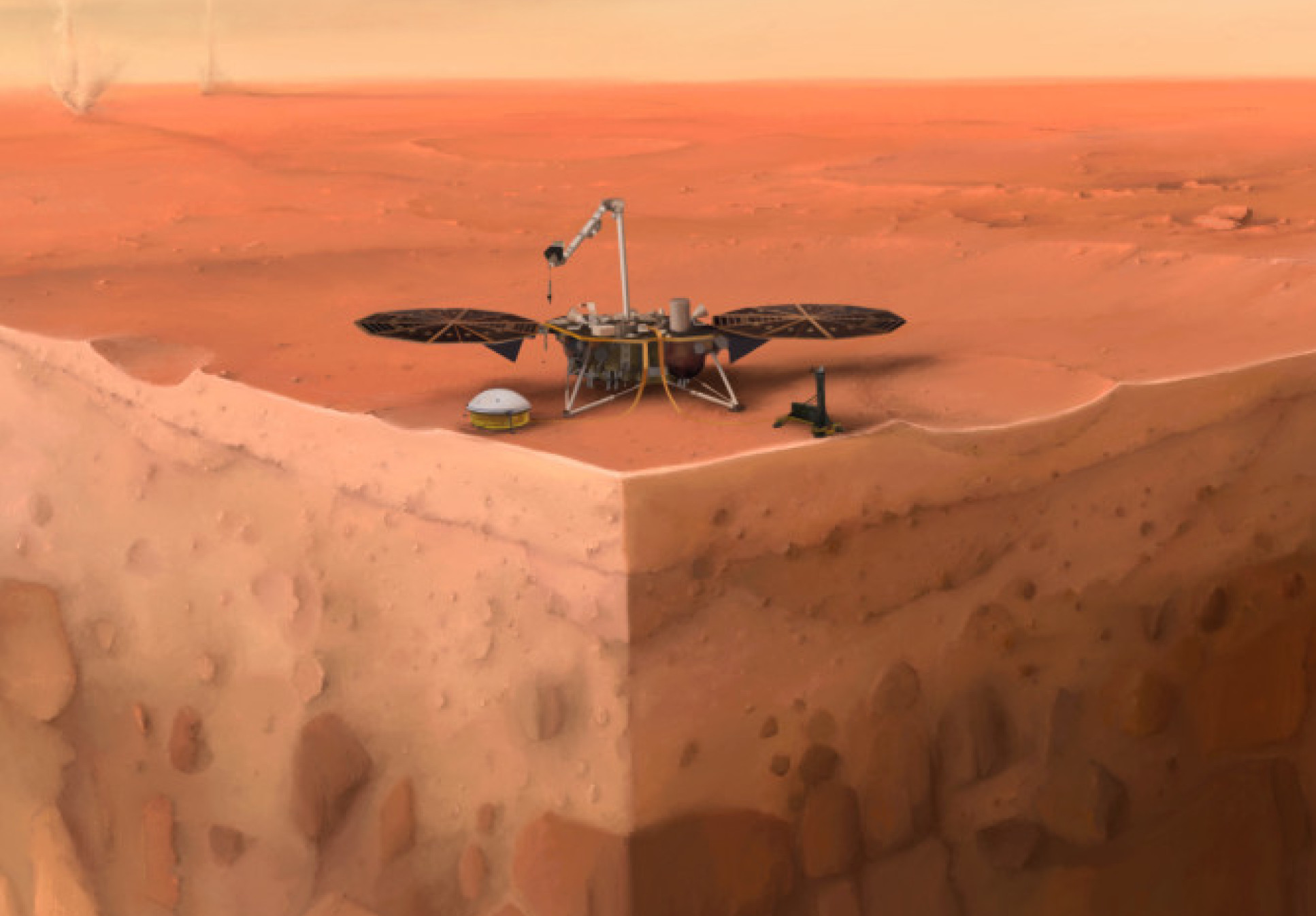

InSight into what makes up Mars

By analysing seismic events, researchers used instruments aboard the InSight lander on Mars to unveil what the hidden interior of the planet looks like.

Understanding what makes up the interior of Mars can help scientists better understand its early evolution.

Imperial scientists were part of a bigger NASA InSight team that looked at marsquakes. As seismic waves travelled through the interior of Mars, some of them were reflected off the planet’s core. By studying these signals, scientists were able to determine the relative size of the core and its likely composition.

Throwing an ‘axion bomb’ in the laws of physics

A research team from Imperial, the Cockcroft Institute and Lancaster University ventured to infinity and beyond when they explored whether the laws of physics break down at singularities.

The team proposed a way that temporary singularities, like black holes which have infinite densities, could violate a much-cherished natural law: the conservation of charge. This law states that the total electric charge in an isolated system always stays the same.

The team showed how axions – hypothetical particles that may explain dark matter –could carry electric charge and disappear into a blackhole, destroying the charge in the process.

Co-author Imperial physicist Dr Paul Kinsler said: “Although people often like to say that physics ‘breaks down’, here we show that although exotic phenomena might occur, what actually happens is nevertheless constrained by the still-working laws of physics around the singularity.” Luckily, the laws of physics will live to see another day!

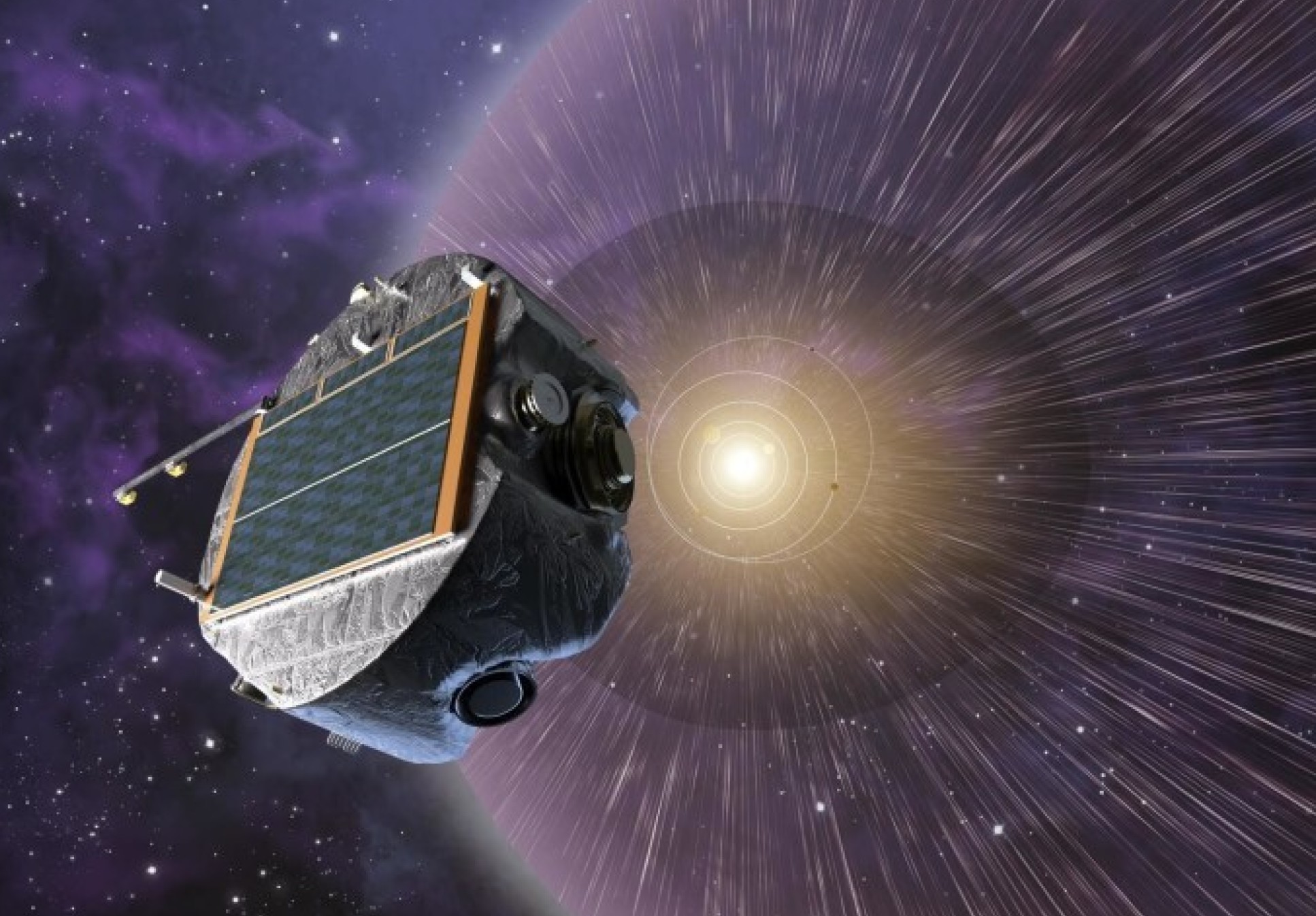

What’s the weather like up there?

A magnetometer built by Imperial physicists will be part of the groundbreaking NASA mission to observe and map solar winds, which are streams of charged particles that the Sun emits.

The mission, known as the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe (IMAP), is due to launch in 2025.

The magnetometer onboard the space probe will measure interplanetary magnetic fields, which are vital to science’s understanding of how charged particles are accelerated and transported throughout the Solar System.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Jacklin Kwan

Faculty of Natural Sciences