‘Breakthrough’ as fusion experiment generates excess energy for the first time

Scientists have hailed a ‘true breakthrough’ as a fusion reaction has successfully generated more energy than was used to create it.

For over seventy years, scientists have been attempting to harness thermonuclear fusion - the power source of stars - to generate energy.

This is a true breakthrough moment, which is tremendously exciting. Professor Jeremy Chittenden

Fusion has the potential to produce vast quantities of clean energy using few resources, requiring only a small amount of fuel and generating limited carbon emissions. Once a fusion plasma is ‘ignited,’ it will continue to burn for as long as it is held in place.

However, fusion reactions have proven difficult to control and no fusion experiment had previously produced more energy than had been put in to get the reaction going.

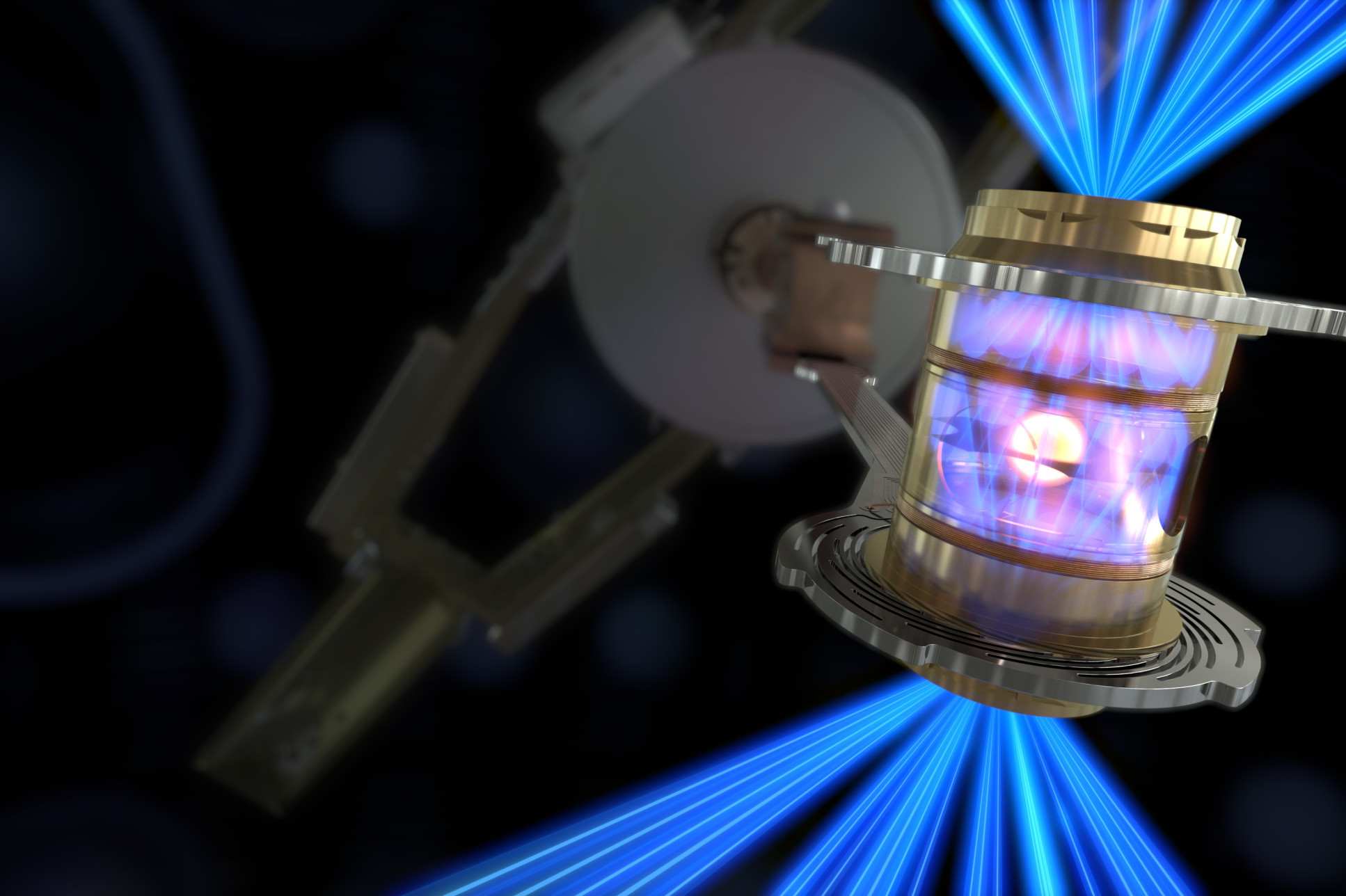

At a press briefing today, it was announced that a fusion experiment at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the US has achieved this ‘holy grail,’ producing more energy than the laser pulse that was used to heat the fuel.

The energy in the laser pulse was 2.05 megajoules – equivalent to the energy of two Mars chocolate bars, or enough to boil six kettles of water. The energy from the fusion reactions was 50% higher than the energy of the laser pulse. It was released in the form of energetic neutrons.

Long sought-after goal

Imperial College London physicists are already helping to analyse the data from the successful experiment, which was conducted on 5 December 2022. Imperial has also produced more than 30 PhD students that have gone on to work at the NIF. The College retains strong links with the facility, and others throughout the world, through the Centre for Inertial Fusion Studies (CIFS).

Professor Jeremy Chittenden, Co-Director of the Centre for Inertial Fusion Studies at Imperial College London, said: “Everyone working on fusion has been trying to demonstrate for over 70 years that it’s possible to generate more energy from fusion than you put in. This is a true breakthrough moment, which is tremendously exciting. It proves that the long sought-after goal, the ‘holy grail’ of fusion, can indeed be achieved. This brings us closer to generating fusion power on a much larger scale.

“To turn fusion into a power source we’ll need to boost the energy gain still further. We’ll also need to find a way to reproduce the same effect much more frequently and much more cheaply before we can realistically turn this into a power plant. It’s hard to say how quickly we might be able to get to that point. If everything aligns we could see fusion power in use in ten years, but it could take far longer. The key thing is that with today’s results we know that fusion power is within reach.”

Professor Steven Rose, also Co-Director of the Centre for Inertial Fusion Studies at Imperial, said: “This wonderful result shows that inertial fusion works at the megajoule scale which gives huge impetus to its development for a power source and as a tool for fundamental science.”

Dr Brian Appelbe, a Research Associate in the Centre for Inertial Fusion Studies at Imperial, said: “As well as being a significant step towards fusion power, this experiment is exciting as it will allow us to study matter at temperatures and densities never previously reached in the laboratory. All sorts of interesting Physics can occur at these conditions, such as the creation of antimatter, and the NIF experiments will give us a window into this world.”

Fusion fuel

The type of nuclear reaction that fuels current power stations is fission – the splitting of atoms to release energy. Fusion instead forces atoms of hydrogen together, producing a large amount of energy, and, crucially, limited radioactive waste.

There are two main ways researchers worldwide are currently trying to produce fusion energy. The NIF focuses on inertial confinement fusion, which uses a system of lasers to heat up fuel pellets producing a plasma – a cloud of charged ions.

The fuel pellets contain ‘heavy’ versions of hydrogen – deuterium and tritium – that are easier to fuse and produce more energy. However, the fuel pellets need to be heated and pressurised to conditions found at the centre of the Sun, which is a natural fusion reactor.

Once these conditions are achieved, fusion reactions release several particles, including ‘alpha’ particles, which interact with the surrounding plasma and heat it up further. The heated plasma then releases more alpha particles and so on, in a self-sustaining reaction – a process referred to as ignition.

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Hayley Dunning

Communications Division

Laura Gallagher

Communications Division