Undetected malaria infection shown to be a persistent problem

by Meesha Patel

Recent evidence recognises the silent and persistent reservoir of parasites as one of the key drivers of continued malaria transmission.

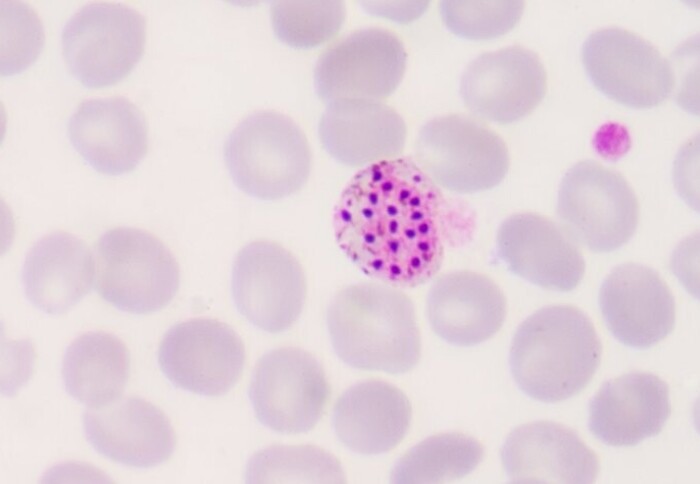

Asymptomatic malaria refers to a condition where individuals are infected with the malaria parasite but do not show noticeable symptoms. This is particularly a problem because asymptomatic infections are sources of parasites for mosquitoes to transmit to others, creating a ‘reservoir’ of infection within the human host.

It is still unknown how some people show this asymptomatic infection state without presenting as an illness. This causes problems when trying to detect and treat these cases to stop further malaria transmission.

A collaborative study between Imperial College London, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and the West African Centre for Cell Biology of Infectious Pathogens (WACCBIP), University of Ghana, explored the possibility that the response of blood cells of children with symptomatic or asymptomatic P. falciparum infections, assessed by genes turned on and off, would reveal how the asymptomatic infection state is maintained. If specific features of the asymptomatic malaria could be detected, they could lead to strategies to identify and eliminate the transmission reservoir, and built into malaria prevention programmes.

"The findings show that it will be difficult to develop simple blood tests which detect asymptomatically infected people based on their immune response." Professor Aubrey Cunnington Department of Infectious Disease

Surprisingly, the results revealed the opposite of what was expected. Whilst symptomatic malaria induces large-scale changes in gene being turned on or off, the analysis of asymptomatically infected individuals showed no difference from uninfected healthy control children. In asymptomatic infections and the uninfected children, no genes were being switched on or off by the infection - in stark contrast to hundreds of genes being turned on and off for symptomatic malaria.

The findings show that parasite numbers are staying below a limit needed to switch on any sort of immune response in the blood, leading to a malaria infection going “under the radar”. This means a human host stays healthy, does not seek treatment and the parasites can survive and be transmitted onwards.

Co-author, Professor Aubrey Cunnington from the Department of Infectious Disease, explained “In many countries with a lot of malaria, asymptomatic infections can greatly outnumber the symptomatic ones. This causes problems because asymptomatic infections are a source of parasites for mosquitoes to transmit to others. The findings show that it will be difficult to develop simple blood tests which detect asymptomatically infected people based on their immune response.”

Dr Julius Hafalla, Associate Professor of Immunology at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine said: “If we want to detect asymptomatic individuals, we would need a more sensitive test for the parasites, which can detect lower levels of parasites than our conventional rapid diagnostic tests and microscopy. So, we are really talking about molecular tests like PCR.”

Diana Ahu Prah, a PhD student who led the work at WACCBIP, University of Ghana, praised this important discovery as a step forward to create new diagnostics “the fact symptomatic malaria produces a strong response in the blood, as compared to asymptomatic cases, means that response could be the basis of future diagnostic tests to distinguish symptomatic malaria from other causes of fever. This would prevent the misclassification of patients who incidentally have parasites but actually have another cause of illness.”

The authors also emphasise the importance of strengthening surveillance efforts, especially in countries nearing elimination, where this recent addition to our understanding of malaria provides a tool in the arsenal to create better diagnostics, vaccines, and treatment.

Adapted from a story on the LSHTM Malaria centre website

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Meesha Patel

Faculty of Medicine Centre