Turning off inflammatory protein extends healthy lifespan in mice

by Ryan O'Hare

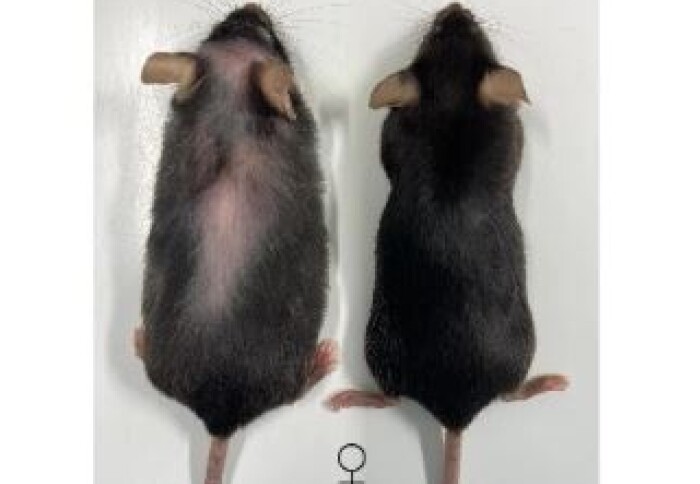

Effects of treatment in mice (Left, no treatment; Right, IL-11 treatment)

Scientists have discovered that ‘turning off’ a protein called IL-11 can significantly increase the healthy lifespan of mice by almost 25%.

Researchers in the UK and Singapore have found that targeting the production of a key inflammatory protein in mice can extend their lifespan, reduce age-related disease and make older animals less frail.

The team, based at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Medical Science (MRC LMS), Imperial College London and Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, tested the effects of IL-11 by creating mice that had the gene producing IL-11 (interleukin 11) deleted. This extended the lives of the mice by over 20% on average.

They also treated 75-week-old mice, equivalent to the age of about 55 years in humans, with an injection of an anti-IL-11 antibody, a drug that stops the effects of the IL-11 in the body.

Extended lifespan

The results, published in the journal Nature, were dramatic. Mice given the anti-IL-11 drug from 75 weeks of age until death had their median lifespan extended by 22.4% in males and 25% in females.

The treated mice lived for an average of 155 weeks, compared with 120 weeks in untreated mice.

While these findings are only in mice, it raises the tantalising possibility that the drugs could have a similar effect in elderly humans. Professor Stuart Cook MRC LMS

The treatment largely reduced deaths from cancer in the animals, as well as reducing the many diseases caused by fibrosis, chronic inflammation and poor metabolism, which are hallmarks of ageing. There were very few side effects observed.

Professor Stuart Cook, co-corresponding author on the study, from the MRC LMS, Imperial College London and Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore, said: “These findings are very exciting.

"The treated mice had fewer cancers and were free from the usual signs of ageing and frailty, but we also saw reduced muscle wasting and improvement in muscle strength. In other words, the old mice receiving anti-IL11 were healthier.

“Previously proposed life-extending drugs and treatments have either had poor side-effect profiles, or don’t work in both sexes, or could extend life, but not healthy life, however this does not appear to be the case for IL-11.

“While these findings are only in mice, it raises the tantalising possibility that the drugs could have a similar effect in elderly humans. Anti-IL-11 treatments are currently in human clinical trials for other conditions, potentially providing exciting opportunities to study its effects in ageing humans in the future.”

The researchers have been investigating IL-11 for many years and in 2018 they were the first to show that IL-11 is a pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory protein, overturning years of incorrect characterisation as anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory.

IL-11 increases with age

Assistant Professor Anissa Widjaja, who was co-corresponding author, from Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, said: “This project started back in 2017 when a collaborator of ours sent us some tissue samples for another project. Out of curiosity, I ran some experiments to check for IL-11 levels. From the readings, we could clearly see that the levels of IL-11 increased with age and that’s when we got really excited!

“We found these rising levels contribute to negative effects in the body, such as inflammation and preventing organs from healing and regenerating after injury. Although our work was done in mice, we hope that these findings will be highly relevant to human health, given that we have seen similar effects in studies of human cells and tissues.

“This research is an important step toward better understanding ageing and we have demonstrated, in mice, a therapy that could potentially extend healthy ageing, by reducing frailty and the physiological manifestations of ageing.”

Previously, scientists have suggested that IL-11 is an ‘evolutionary hangover’ in humans, as while it is vital for limb regeneration in some animal species, it is thought to be largely redundant in humans.

Chronic inflammation and frailty

However, after about the age of 55 in humans, more IL-11 is produced and past research has linked this to chronic inflammation, fibrosis in organs, disorders of metabolism, muscle wasting (sarcopaenia), frailty, and cardiac fibrosis. These conditions are many of the signs we associate with ageing.

When two or more such conditions occur in an individual, it is known as multimorbidity, which encompasses a range of conditions including lung disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, vision and hearing decline and a host of other conditions.

Professor Cook added: “The IL-11 gene activity increases in all tissues in the mouse with age. When it gets turned on it causes multimorbidity, which is diseases of ageing and loss of function across the whole body, ranging from eyesight to hearing, from muscle to hair, and from the pump function of the heart to the kidneys.”

Tackling multimorbidity

Multimorbidity and frailty are acknowledged to be among the biggest global healthcare challenges of the 21st century, according to many leading health bodies, including the NHS and the World Health Organization.

Currently, no treatment for multimorbidity is available, other than to try to treat the separate multiple underlying causes individually.

The scientists caution that the results in this study were in mice and the safety and effectiveness of these treatments in humans need further establishing in clinical trials before people consider using anti-IL-11 drugs for this purpose.

The study was primarily funded by the National Medical Research Council (Singapore) and MRC in the UK.

-

‘Inhibition of IL-11 signalling extends mammalian healthspan and lifespan’ by Widjaja, A.A., Lim, WW., Viswanathan, S. et al. is published in Nature. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07701-9

This article is based on materials from the MRC LMS.

Image credit: MRC Laboratory of Medical Sciences / Duke University

Article supporters

Article text (excluding photos or graphics) © Imperial College London.

Photos and graphics subject to third party copyright used with permission or © Imperial College London.

Reporter

Ryan O'Hare

Communications Division