The optical microscope is one of the most widespread biophotonics tools and has allowed researchers to study biological processes down to the cellular level since the cell was first described by Robert Hooke in 1632. Indeed, for much biological research, “microscopy” has become almost synonymous with “imaging”, although many concepts developed for microscopy are being translated to optical imaging at larger scales. Today there is tremendous progress extending the limits of optical imaging in terms of spatial and temporal resolution and with respect to the functional “content” that optical images can provide. Increasingly these approaches are being applied to high throughput automated imaging for drug discovery and systems biology and to in vivo imaging for preclinical and clinical research. For studies of disease mechanisms, microscopy is increasingly evolving from imaging thin layers of cells on a coverslip to studies of 3-D cell cultures, which provide a better representation of the in vivo context, and to imaging of cellular processes in live organisms – from worms and fruit flies to humans.

Fluorescence is the phenomenon whereby a sample absorbs incident photons (such that electrons are excited to a higher energy level) and emits photons (fluorescence) at a longer wavelength. Many naturally occurring molecules are inherently fluorescent – these are described as fluorophores. However, most biological molecules do not fluoresce in the visible spectrum and often biological molecules such as proteins, are labelled with a convenient fluorophore “tag” that is readily excited by visible light sources and can be directly viewed or detected using a camera. These fluorescent tags are often based on dye molecules that can be chemically attached to biological molecules of interest with great selectivity. By labelling different species of biological molecule with different colour tags, different biological molecules can be distinguished – thus fluorescence enables optical molecular imaging. Some biological molecules are themselves inherently fluorescent and the emission of these endogenous is fluorophores termed “autofluorescence”.

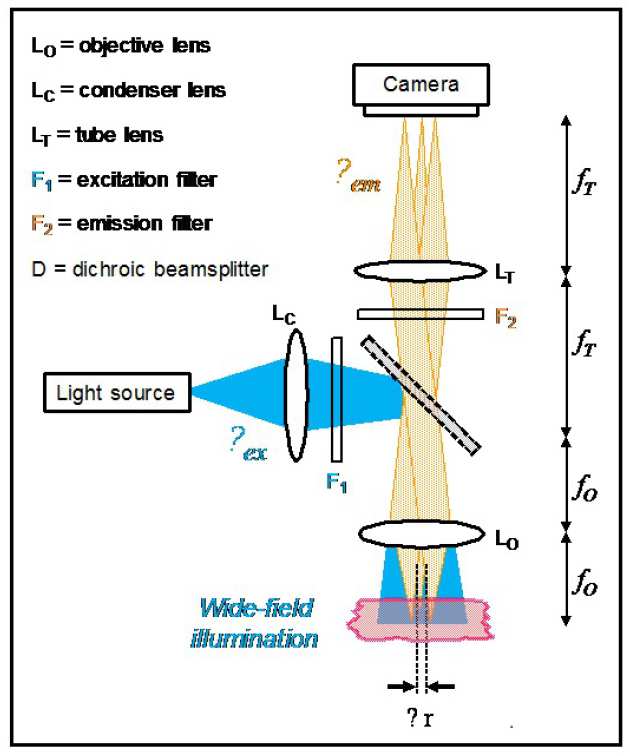

Because the fluorescence comprises photons at a longer wavelength than the excitation radiation, the fluorescence signal can be easily separated from the excitation light using a beamsplitter and/or filters. Unlike other forms of microscopy that utilise reflected or scattered light, this means that very weak fluorescence signals – down to a single photon – can be detected. In turn, this means that a single fluorescent tag can be imaged – enabling visualisation of the distribution of individual biological molecules. The figure shows the most common form of fluorescence microscope where excitation light is reflected by a dichroic beamsplitter and illuminates the field of view to produce fluorescence at a wavelength that is transmitted by the dichroic beamsplitter. The fluorescence image is formed by the action of the two lenses, known as the objective lens, which captures the light from the sample, and the tube lens that forms the image at the camera. The magnification of the microscope is given by the ratio of the focal length of these lenses: fT/fO. The best possible (transverse) spatial resolution of this microscope is given by ~λem/2 NA where λem is the wavelength of the fluorescence emission and NA is the numerical aperture of the objective lens. This formula was presented by Ernst Abbe in 1873 and represents the diffraction-limited performance that is limited by the wave nature of light.

Fluorescence microscopy has enjoyed a particular renaissance over the last decade, partly driven by advances in light source and detector technologies and partly due to advances in labelling technologies such as fluorescent proteins that can tag specific proteins of interest using genetic engineering. This can enable the labelled proteins to be visualised in living cells or organisms - and allow them and their dynamics to be studied in real time. By labelling different proteins with fluorophores emitting at different wavelengths, spectrally-resolved fluorescence images can be used to provide information about temporal and spatial colocalisation of the different labelled proteins, which can provide insights into molecular processes. Increasingly, however, fluorescence instrumentation aims to provide more information than just the distribution of specific fluorescent molecules. Often fluorescence signals are analysed spectroscopically to provide information on the local fluorophore environment, to study interactions of biomolecules and to distinguish different contributions from complex mixtures of fluorophores – as often occur in the “autofluorescence” of unlabelled biological tissue.

In the Photonics Group, we are developing many new fluorescence-based technologies including optically sectioned fluorescence microscopes for 3-D imaging, automated fluorescence microscopes for high content analysis (HCA) of cell signalling processes to study disease mechanisms and super-resolved microscopy to provide imaging beyond the conventional diffraction limit. We are also developing fluorescence endoscopy for in vivo imaging and fluorescence tomography for 3-D imaging of larger samples including live organisms.