Who was Constance Tipper?

A glimpse into the life of an extraordinary material scientist

In 1978, the US government declared an ordinary-looking cargo ship, a liberty ship from Word War 2, to be an American national monument. Operational to this day, the ship was one of the few to survive the D-Day Armada.

The ship was also one of the first to move away from traditional riveting techniques to the new ship-building technique of welding. This technique had an incredible advantage during World War 2, as Liberty ships could be built in five days: twenty times faster than their contemporaries.

Liberty ships were key in carrying vital supplies across the Atlantic to British armies, yet the first few liberty ships had one fatal flaw. They would crack dramatically due to the freezing temperature of the ocean, sometimes breaking in half. This was a significant issue during World War 2, and the problem was presented to a researcher named C.F. Tipper.

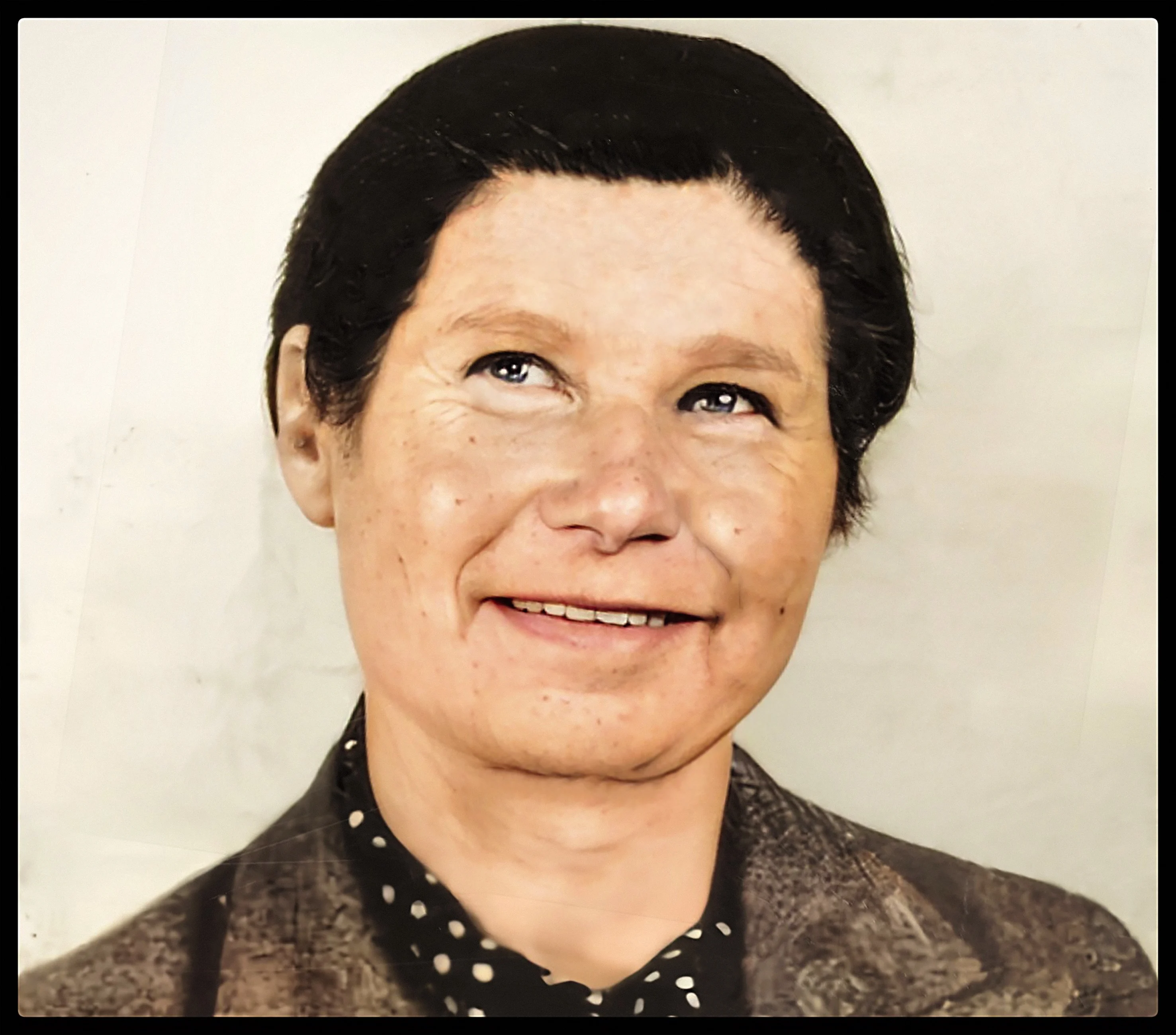

Who was Constance Tipper?

Constance Fligg Tipper (nee: Elam) was born in 1894 in New Barnet, Hertfordshire. She studied Engineering at Newnham College, Cambridge, in 1912 and was among the first women to take the Natural Sciences Tripos.

After working briefly at the National Physical Laboratory, metallurgical department, in Teddington, Constance joined the Royal School of Mines as a Research Assistant to Sir Harold Carpenter. Her research investigated the new science of the strength of metals.

Constance Tipper also collaborated with the famous scientist GI Taylor, where she investigated crystal deformation under strain. Her research on alumina crystals laid the foundation for modern dislocation theory, and she was also the first to utilise scanning electron microscopy to investigate fractures in metallurgical research.

Constance left the Royal School of Mines in 1929 and established herself as a leader in the engineering field at the University of Cambridge. Over the years, she became highly regarded for her groundbreaking work on brittle fracture in Liberty ships during World War 2 and for developing the "Tipper Test."

What was the Tipper test?

The origins of the test started with Liberty Ships. Liberty Ships were built in the UK and USA during World War 2, and they were vital for transporting essential supplies across the Atlantic. These ships were also the first to be all welded rather than riveted.

However, brittle fractures soon became an urgent naval problem, as several Liberty ships started to develop large cracks while in freezing sea conditions. Constance Tipper was tasked with discovering why these ships were cracking - and quickly.

Many had assumed this breakage resulted from the welding method or fabrication process used to make the ships. However, this was not the case.

Constance's research discovered that the root cause of the sudden and catastrophic failures of the Liberty ships was due to the fracture in steel which became dangerously brittle in low temperatures. The ships were therefore susceptible to brittle failure when crossing the Atlantic.

To measure the brittleness of materials, Tipper developed the "Tipper Test," which is still used today.

The test measures the ductile-brittle transition temperature of materials, the temperature at which a material changes from being flexible to breaking suddenly and without warning. This is now the standard method for determining this form of brittleness in steel.

Constance published her results in her book The Brittle Fracture Story (1962).

As a result of her research, manufacturers began improving both the quality of the steel and annealed welds used in shipbuilding.

Fighting for recognition

Constance Tipper published over 80 papers and received numerous awards throughout her career, including the Frecheville Research Fellowship in 1921. In addition to working at the Royal School of Mines, she held positions at prestigious institutions such as the Davy Faraday Laboratory, the Royal Institution, and the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge.

Tipper was only recognised 32 years after she started her research. In 1949, she was awarded the academic title of Reader when her male colleagues vacated their positions to fight during World War 2. At the same time, she was made a full Fellow of the Engineering Faculty of Cambridge University, a first for a woman.

There were also instances where she received a different recognition than her male colleagues. For example, in 1923, the Royal Society invited two researchers named G.I. Taylor and C.F. Elam to discuss their groundbreaking work at the annual Bakerian Lecture, followed by dinner at the Royal Society Dining Club.

However, they had not realised that the “C” stood for Constance, which led to an awkward encounter as the dining club was not open to women.

Constance is known to have politely declined the invitation and received a box of good chocolates from the Royal Society as a way of apology.

An important legacy

"Her vigour in prosecuting her work in an extremely male preserve will always be remembered and admired by those who came into contact with her”

Tipper's pioneering work has paved the way for future generations of scientists and engineers, and she remains an inspiration to modern scientists.

Her research helped to advance our understanding of the properties of materials and played a crucial role in developing safer and more reliable engineering structures, such as bridges, aircraft, and nuclear power plants. Additionally, her work has supported further research into the behaviour of materials under stress, leading to the development of new technologies and techniques for testing and analysing materials.

Alongside her research, Tipper was committed to promoting the study of materials science to young people, particularly women and encouraging them to pursue careers in science and engineering.

Although she officially retired in 1960, she continued working well into her seventies as a consultant at the Barrow shipyards and on metal bridge construction.

Constance Tipper is an inspiration to us all.

References:

Obituary for Constance Tipper, The Independent.

Women at Imperial College Past, Present and Future, Anne Barrett, Imperial College Archivist & Corporate Records Manager, World Scientific, 2017

125 years of Engineering Excellence: Constance Tipper, University of Cambridge.

Constance Tipper, Wikipedia.