26 Nov 2014 to 9 Jan 2015

|

Artists in this exhibition: |

Chris Shaw |

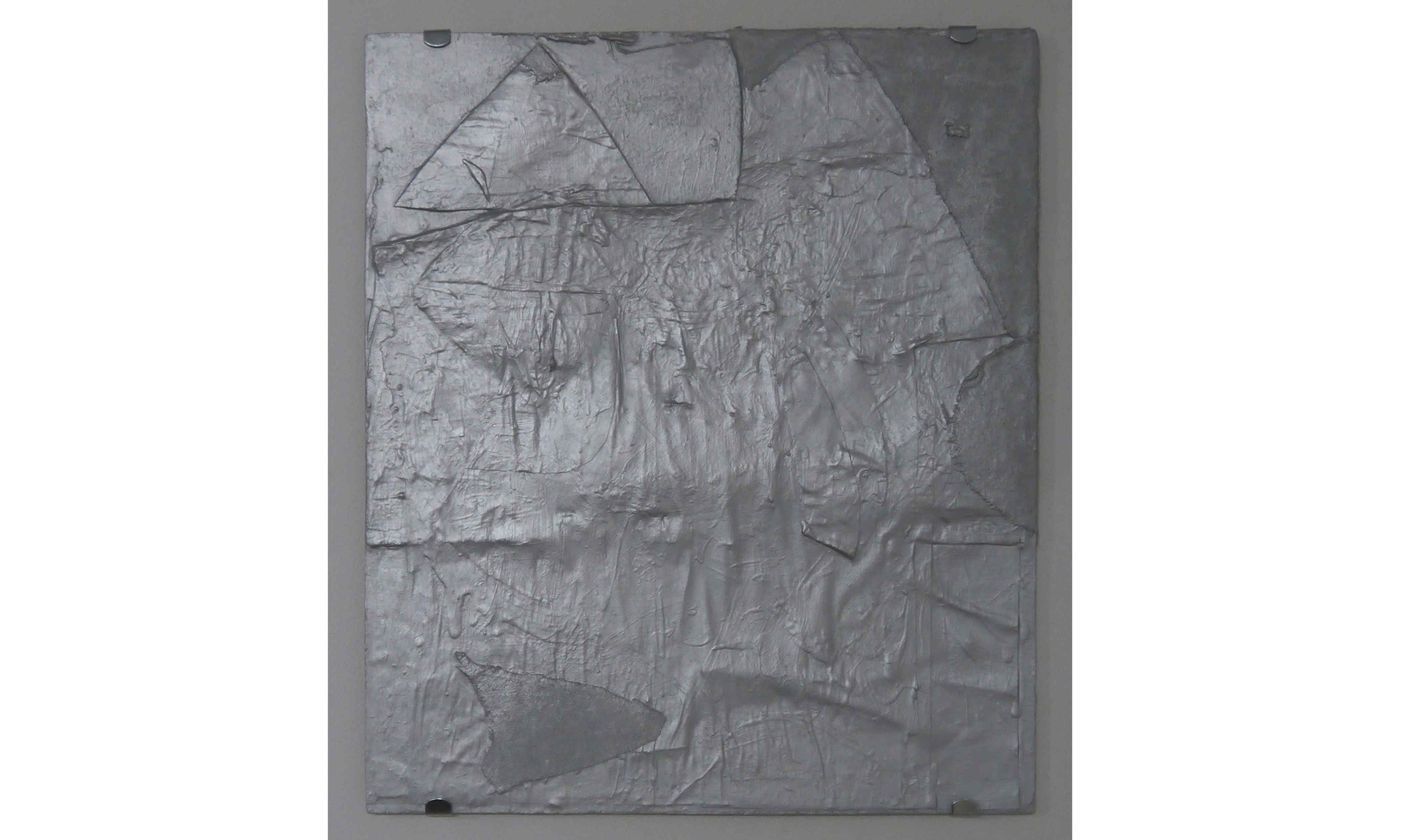

Chris Shaw’s work is deceptive. I am sitting in my studio the day after visiting the artist at his studio in Weymouth. I am looking at a fragment of a painting he has given me as a memento. It is a composition, about 14 x 14cm in size, of what appears to be some scraps of silver, pink and black canvas stapled together. As I look closer at the canvas sample I turn it over and realise that it is in fact the cast of the surface texture of canvas built up using layers of acrylic paint. This is an idiosyncratic game to play, common to Shaw’s practice.

In one of his new series’ Shaw has used a painting that he was given by artist and friend Katy Moran, which she felt was a failure, and cast it several times in jesmonite, then painted each of the casts in different monochromatic, synthetic, metallic hues. The group is collectively titled ‘Catamaran’ - a punning reference to Moran’s name and also to a kind of boat - perhaps located in the harbour outside his studio – and connoting the stabilising process that making the work had on their friendship. Shaw sublimates his own personal narratives within art historical ones.

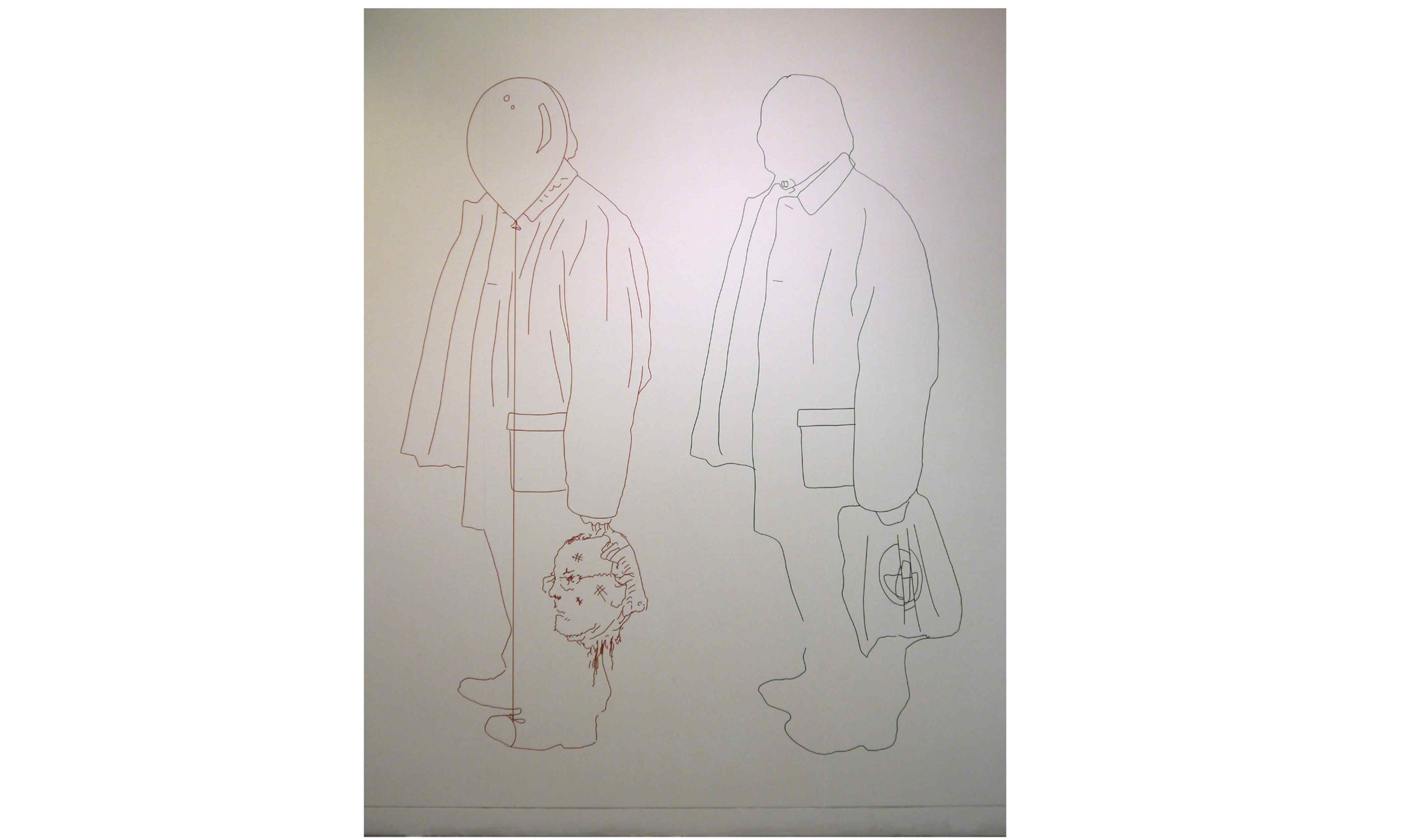

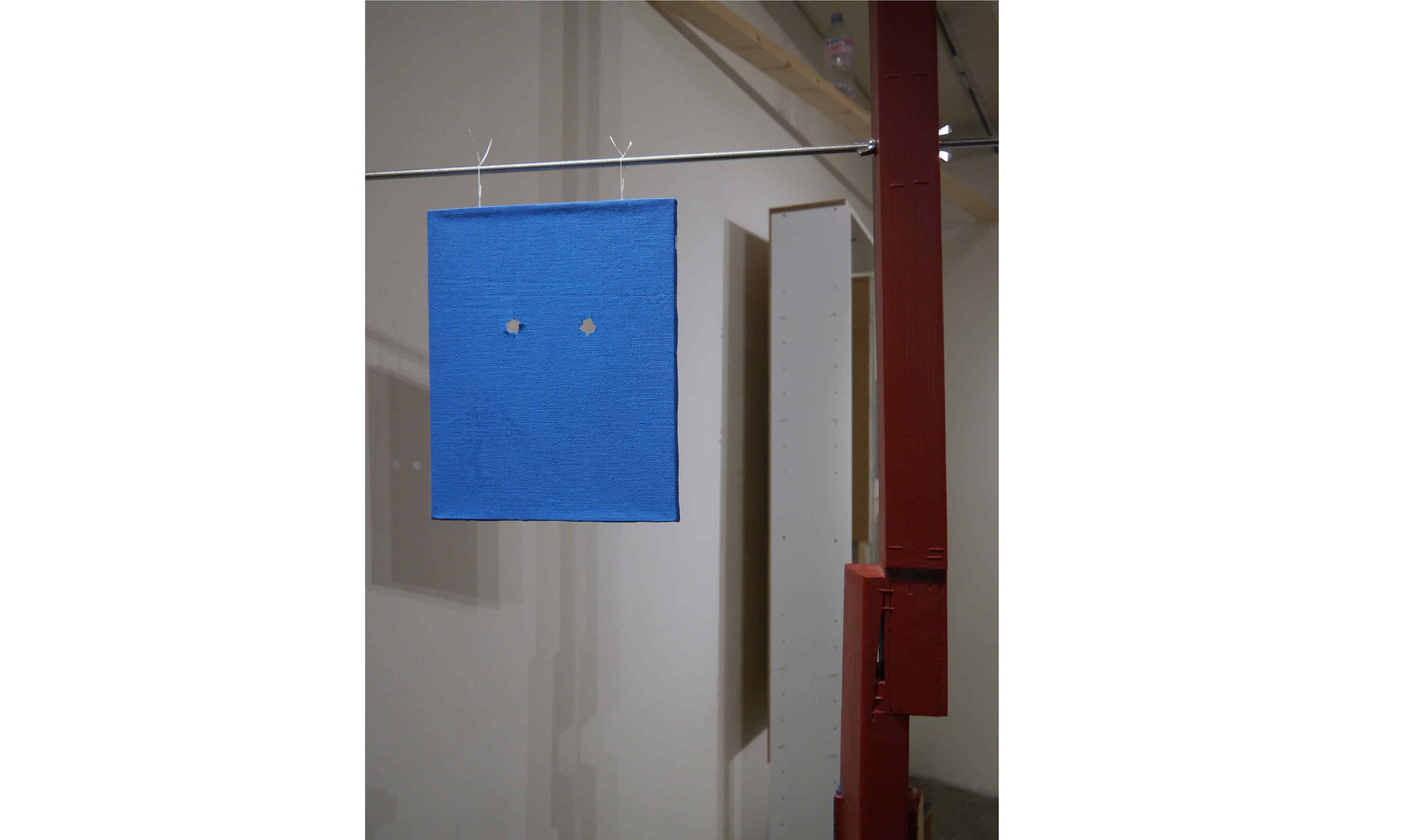

Nevertheless, Shaw’s oeuvre is not made up of one-liners. He is working on a number of works simultaneously, conceived of as a suite of parts that interact like instruments and acts within a visual orchestra. His work forces us to constantly move between pieces to compare and contrast elements in order to grasp the full effect. We are drawn close to his work to examine the traces of paper left on a wall when a staplegunned poster has been pulled down or to look at the globs of chewing gum smushed against a wall. Shaw’s works are terse and ironic, witty decoys that lure us into mental games as subtle as their surfaces.

For him, like many artists before him, the studio has become a self-reflexive space to ponder in its own right. His process brings to mind artists such as Bruce Nauman who have filmed the studio at night, with rats crawling around, or works such as 'In the Studio' (1982) by Jasper Johns that translate the device of the ‘play within a play’ into the context of painting. It is no coincidence that Shaw studied anthropology for a while. He performs as detective on his own practice, looking over his own shoulder to identify habits and intervene in them; framing, quoting, parodying, ironising, deflating, sentimentalising and reframing in order to test and understand his own thinking process further. It is an open-ended activity. The studio has become an archaeological site in which everything is a potential fragment and a potential whole within some ongoing recycling project.

However, for Shaw the distinction between the studio and home are blurred. He began making the works in this exhibition in a room in the house he was living in in London and then transferred them to a studio in Weymouth – a larger space in which he can get some physical and critical distance on things in order to restage them, eventually in a gallery. This collapse of domestic and professional space is generative for Shaw, as it has been for many other artists and musicians, often born out of necessity - it becomes a fertile ground for subject matter.

Chris Shaw is an autoethnographer. His approach to making art is diaristic. His sculptures are often codified and operate within a hermetic realm that can initially, at least, be difficult to access, but once inside becomes rich and complex. It is not so much that his work is art about art, instead that art, and Modernism in particular, functions as a motif within his oeuvre. Over time Shaw’s work has been characterised by the use of what comes to hand as the starting point for his investigations. This is then combined with an obsessive quality to produce works that are cathartic for him and his audience. His process brings to mind Kate Bush’s song ‘Mrs. Bartolozzi’, the mantra of which “washing machine, washing machine” transforms the mundanity of suburban domesticity into a kind of ritual process. With his own mantra ‘assemble, build, join, unite, add, link, construct, combine’ Shaw becomes a kind of Bedsit Balthus.

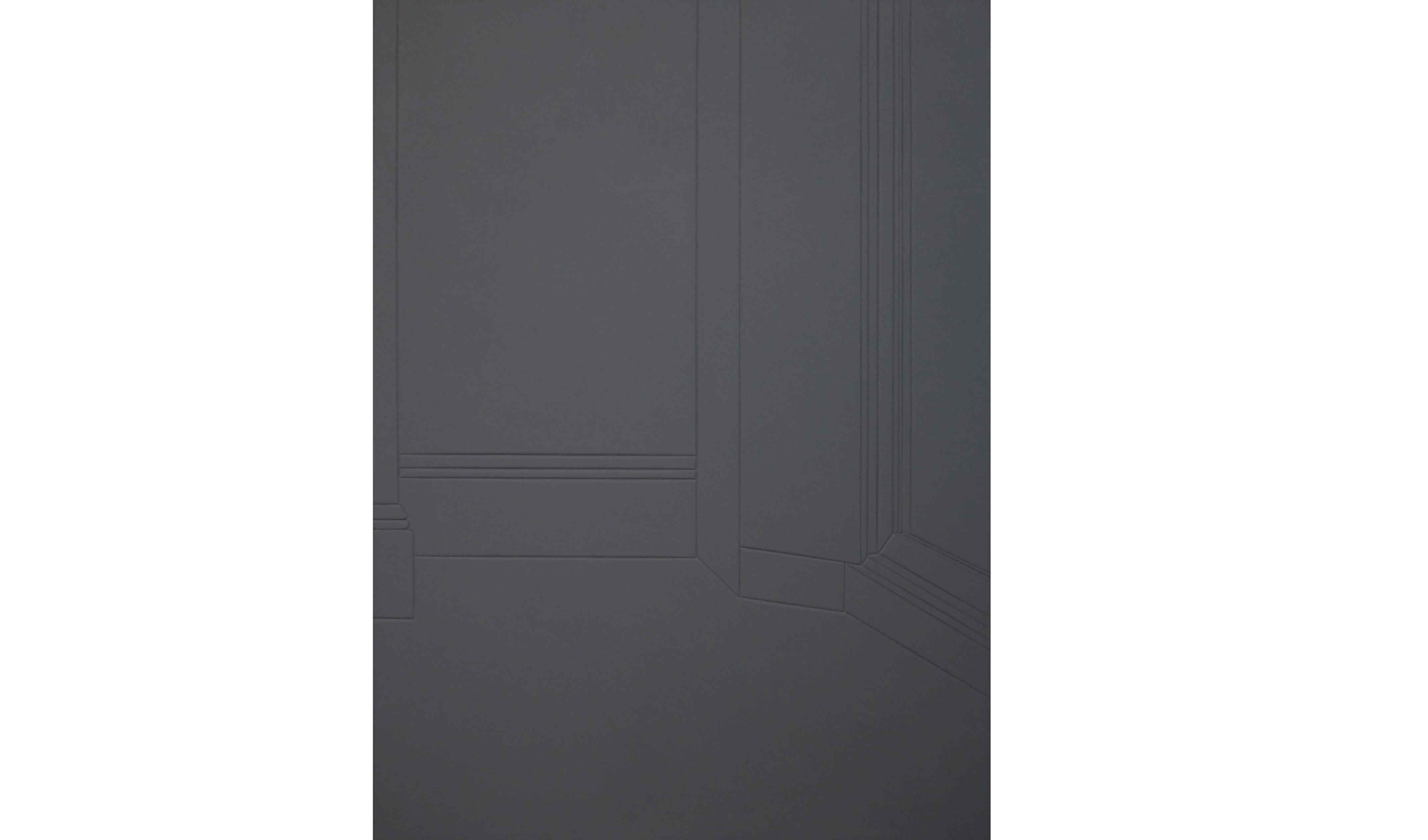

Furthermore, melancholy abounds in Shaw’s work. His is a form of ‘neo kitchen sink realism’ that brings post-war Britain to mind. In one painted relief he draws on a space depicted within a Lucien Freud painting from 1951 entitled ‘Interior at Paddington’. Emptied of the figure and painted a flat “undercoat grey” the piece also brings Jasper Johns to mind. Indeed, Shaw draws on Johns’ many grey paintings for inspiration not only for their appearance but also for their narrative approach. There is a small Johns painting called ‘No’, which is covered in a varied flurry of grey encaustic paint marks and attached to the surface, dangling down on a wire from the top, is the word NO in metal letters. The painting refers to the break up of Johns’ relationship with Robert Rauschenberg. It is oblique but evocative. This methodology is not a million miles away from Shaw’s ‘Catamaran’ piece, which channels a similar kind of narrative energy.

The central motif within this new suite of works is the fireplace. Like many of Shaw’s motifs it is repeated, as a theme and variation, in a range of guises. In one iteration Shaw takes apart an electric fire, showing us the workings behind the scenes – revealing a fan and some strips of fabric wobbling in parallel lines something like a kinetic version of Bridget Riley’s op art waves. In another piece, based on a fireplace that Shaw’s partner built in their former London home, the fireplace is recreated in MDF almost as a monument to their relationship. Shaw plays with the mythology of the hearth as the centre of the home as well as the centre of the relationship. His hearth is depicted not so much as a warm fire than as a locked safe. He has inverted the symbolism to create something sinister. The newspapers stashed beneath Shaw’s recreation fireplace suggest kindling and give the sculpture the association of being potential bonfire. Shaw’s apparently innocuous objects reveal themselves to be conceptual Molotov cocktails, and we, as the protagonists in his dramas, become the cerebral terrorists.

John Walter September 2014