New research suggests newspaper reporting can be used to spot recessions early

There is a growing body of research that explores the question of whether the tone and volume of economic reporting can affect people’s perceptions, and consequently have a significant impact on the business cycle.

One channel through which this can happen is what Nobel-prize winning economist Robert J. Shiller calls “narrative economics”. It is the idea that stories, transmitted by news media, word of mouth, or social media can spread very quickly – “go viral” – and significantly impact people’s economic decisions, both individually and collectively. Studying these narratives can, according to Shiller, “vastly improve our ability to predict, prepare for, and lessen the damage of financial crises, recessions, depressions, and other major economic events”.

Bordalo, Gennaioli and Schleifer suggest another possible channel: people may wrongly overweight future outcomes when faced with a flow of new information. Or investors might have limited attention and rationally only update their expectations when news become more prominently mentioned (what Sims, and Mankiw and Reis call “rational inattention”).

This literature suggests economic agents are more likely to pay attention to events that are more frequently mentioned in the media. With this motivation in mind, we built a simple and transparent measure based on the frequency the trigger-word “recession” is reported in major newspapers. We showed that such an index, especially when based on specialised newspapers like the Financial Times, can provide a useful high-frequency, real-time coincident and leading indicator of US economic activity.

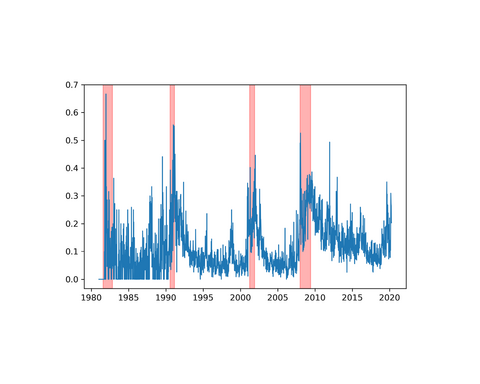

This is illustrated in Figure 1, which plots at weekly frequency how often the word “recession” appears in articles published in the Financial Times between 1980 and March 2020. This index is a raw measure normalised by the number of articles discussing the US economy and is therefore relevant for the U.S. business cycle. In Figure 1, the shaded areas are NBER recessions, which are usually dated with a substantial lag, especially relative to the onset of the recession. Figure 1 shows how the media-based index can be a useful indicator of economic activity.

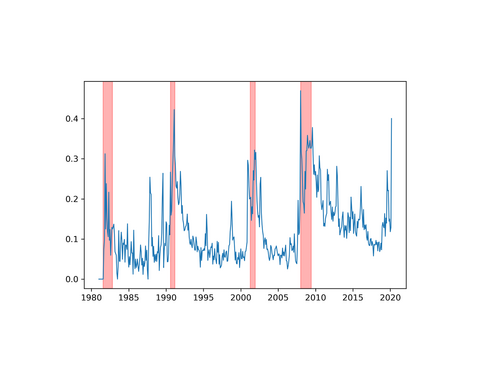

We extended this index by considering the number of times the word “depression” appears in these articles. We plotted the monthly frequency version of this index in Figure 2. This was available on 1 April 2020 and shows the recession probability for March 2020 in the US is already very high by historical standards, providing strong, quantitative, real-time evidence for the presence of a recession in March 2020.

For comparison, around three weeks later, on 20 April 2020, the March Chicago Fed National Activity index was released, showing elevated recession probability for March 2020. The Chicago Fed index is based on different measures from the ones we analysed, and provides consistent evidence with our measure, with a three-week lag. These results illustrate the value of analysing text as data for predictive business cycle analysis.

This research programme is part of a broader programme to analyse and quantify the information available in text. Baker, Bloom and Davis provide a seminal contribution in measuring economic policy uncertainty using similar methods. We have shown how this approach can be extended to provide a real-time measure of aggregate economic activity that can help guide policy and business decisions.

Analysing text as data to guide policy and investment decisions more broadly is a useful direction for future research, employing quantitative techniques from machine learning to guide policy and business decisions.

This article draws on findings from “Media and Business Cycles” by Salim Baz (Imperial Business School), Lara Cathcart (Imperial Business School) and Alex Michaelides (Imperial Business School, Centre for Economic Policy Research).