Total venture capital and private equity investment in renewable energy grew to $3.4 billion in 2015. That’s a small fraction of the assets under management by private equity in total (which sat at $2.4 trillion USD at the middle of last year), but still an impressive – and growing – tally. While the majority of private equity dollars are allocated to fossil-fuel focused businesses, many of the largest generalist funds maintain dedicated energy-focused investment vehicles that include renewable electricity projects. Examples in this grouping include Blackstone’s Onyx Renewable Partners, TPG Alternative & Renewable Technologies, and KKR Infrastructure and Real Assets. There are also exclusively energy-focused firms (such as Denham Capital Management), and even firms with exclusively clean technology mandates (such as Hudson Clean Energy Partners).

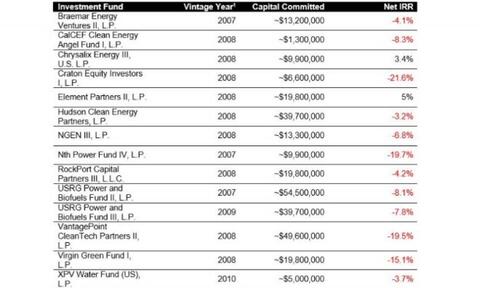

Despite the rapid growth of the renewables industry, the track record for private equity investments in the space is generally considered to be poor. This is illustrated by the performance of the California Public Employees System (CalPERS) Clean Energy and Technology Fund, which recently showed negative returns in 12 out of 14 commitments:

Table 1: CalPERS Clean Energy and Technology Fund Performance Source: Adapted from CalPERS as of November 17, 2016

Given the weak performance highlighted above, it is unsurprising that some PE investors have dismissed the entirety of renewable energy, with the Financial Times going so far as to declare private equity investment in renewables a ‘fad’. The recent U.S. election result of Donald Trump has thrown further uncertainty into the overall sector’s profitably, with many renewable energy stocks cratering after the results were announced.

However, investors need not give up hope yet. Structural shifts within the industry make the selection of 2006-2009 vintage funds – the benchmark by which the industry is largely judged – a poor indicator of future performance for the sector. In understanding this underperformance, investors will need to assess private investments in renewable energy on their idiosyncratic merits, as these investments will be operating in a very different market environment compared with the previous decade.

The first step to a clear perspective on the future of PE in the renewables sector is to start by disaggregating Venture Capital (VC) and PE, which are often grouped under one heading, but in reality have very different mandates and profitability potential.

VC vs. PE

VCs are most well-known for investments in information technologies and biotechnology – sectors which often come with minimal barriers to entry, enormous potential for innovation, and relatively low upfront costs. However, in the mid 2000s, a combination of high energy prices, rising awareness regarding climate change and enabling legislation resulted in a surge of VCs raising funds focused on clean energy technology (or “cleantech”). Many investors believed that the society’s growing need for energy represented an exciting growth opportunity for their VC fund management skills, with the side benefit of alleviating the threat of climate change. Money poured in, and expectations rose accordingly.

The results, however, fell short of expectations, and a recent MIT study noted that “cleantech companies developing new materials, hardware, chemicals, or processes were poorly suited for VC investment because they required significant capital, had long development timelines, were uncompetitive in commodity markets, and were unable to attract corporate acquirers”. Applying the venture capital model to energy’s high barriers to entry, tendency to evolve in increments, and high upfront capital expenditures was, in hindsight, bound to be problematic. Energy history is laden with cases of goals (in new technologies, in electricity plant configurations) that were either abandoned or fell short of their normative attainments, and the VC plunge of the last decade is no exception.

This strategy contrasts substantially with PE funds who, by virtue of investing in more established technologies, typically have a lower risk profile than VCs. PE investors generally focus on providing capital to more mature businesses seeking to grow and execute their business strategies. These funds can also facilitate buyouts of existing companies, or purchase distressed businesses and restructure them.

Current vs. past funds

The second area for consideration when assessing the role of PE in today’s renewable energy market is to recognize the distinction between current and past funds (as previously stated, the track record for private investment in renewables is largely evaluated based on the performance of funds raised between 2006 and 2009). However, in assessing the attractiveness of the sector, it is important to better understand how the market environment has evolved through various vintages. Three principal drivers of under-performance – investment focus, maturity of the industry, and exit opportunities – stand out as worthy of consideration. In all three factors, the risks are substantially reduced today.

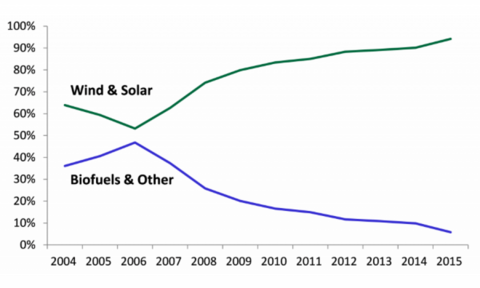

First, early vintage funds invested substantially in biofuels and technology, both of which proved to carry substantial risks. The former – a fuels business – is inherently volatile, subject to fluctuations in terms of regulatory environments and the prices of both inputs and outputs[1]. Technology did not fare much better. Many companies were highly dependent on uncertain outcomes as they developed “first-of-a-kind” products; as Peter Thiel and Blake Masters note in a recent book release, it is not usually the initial arrival to a business concept that fares best. Unsurprisingly (and as shown in Figure 1), the share of biofuels and investments excluding wind and solar peaked in 2006, and has since declined.

Figure 1: Investment by Technology (2004-2015) Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 2016

Second, the relative immaturity of the clean energy industry in 2006 meant that investments were overwhelmingly dependent upon government subsidy. The emerging subsidy programs targeting clean energy were highly effective in terms of sparking an investor response – investment surged in markets (such as Germany, Spain, and Italy) where feed-in tariffs were introduced. However, policies were heterogeneous, with varying tariff levels and mixed abilities to control deployment of capacity. In select countries, this resulted in large support payments to clean energy generators which, during the recession of 2009, proved unsustainable for strained government budgets and households with diminished incomes. The well-documented retroactive changes in tariffs which followed led to asset impairments for many PE investments in these markets.

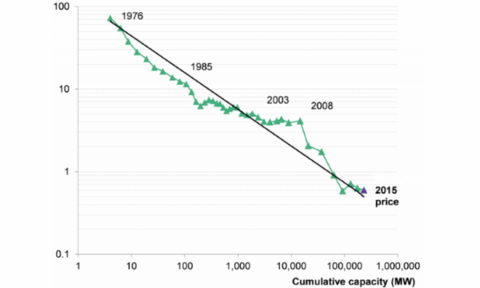

A fortunate outcome of the scaling of the industry through its rapid expansion in the 2000s has been dramatic reductions in the costs to generate power (levelized cost of energy or “LCOE”) from onshore wind and solar PV. Solar PV module costs, for example, have averaged a 24% decline for every doubling of capacity, resulting in an 80% cost decline since 2008 (see Figure 2). The International Renewable Energy Agency forecasts an additional 59% decline and 26% decline for the LCOE of solar PV and onshore wind, respectively by 2025 (IRENA, 2016).

Figure 2: Solar PV Module Cost Curve ($/W) Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 2016

These cost reductions have significantly reduced the public subsidy required to pursue clean energy policies, especially when combined with improvements in systems performance and efficiency. Globally, clean energy polices have further evolved to shift from a fixed premium pricing structure to competitive tenders. These shifts have provided significant stability to the industry by reducing the risk of retroactive policy changes (which resulted in markets where support levels significantly exceeded levelized costs of generation).

The third factor contributing to the underperformance of clean energy investments was a lack of exits Again, this has changed markedly since 2009, largely due to the growth of wind, solar PV and biomass as established generation technologies. These technologies often have long-term offtake agreements which, once operational, allow the projects to generate stable and predictable yields. Private equity is well positioned to fund development risk and exit projects (once operationally de-risked) to a variety of buyers, including utilities, sovereign wealth funds, infrastructure funds and publicly traded “yieldcos”. The latter has emerged only within the past three years, allowing public investors to access portfolios of renewable generation assets which were previously inaccessible due to size, concentration risk or liquidity concerns. Infrastructure funds, another form of private equity capital which targets lower-return assets relative to PE, have become increasingly interested in wind and solar PV assets as their risks have become better understood. Deal volume assessments indicate a promising future for renewables; indeed, the sector comprised the largest source of infrastructure deals in 2015, with 295 transactions (Preqin, 2016).

Conclusion

Looking forward, the future challenge for PE in renewables is arguably less related to shifts in government policy, but rather achieving high returns in a more mature market. As with PE investments in other sectors, generating solid risk-adjusted returns will depend on partnering with excellent management teams, persistence in project execution, access to proprietary deal flow and financial innovation. There are no obvious reasons why PE investors will be unable to continue to hold these competitive advantages. In a world of declining generation costs and increased awareness of climate change, savvy investors should be attuning themselves to a reality where renewables may not only be the most environmentally-friendly option, but also among the most profitable.

[1]The vintage (or “founding”) year of these funds obviously overlapped with the Great Recession, in which access to liquidity was severely constrained within the global financial sector as a whole.

[2] The latter uncertainty is especially problematic given the weak correlation between input prices (corn and soybeans) and the output (e.g. transportation fuels)).

Joel Krupa is a visiting researcher at the Centre for Climate Finance & Investment at Imperial Business School.